Art imitating life?

This morning, as I slumped in bed trying to fend off the tail-end of my head cold, I was reading through assorted interesting articles that had caught my eye over the last few days. One of these was a piece from The Independent, first published in 2013, in which the German painter Georg Baselitz was being taken to task for saying that ‘women lack the basic character to become great painters’, and thus on principle, only men can be great artists. As the journalist outlined the various angry responses to Baselitz’s remark (the best of all being Prof. Griselda Pollock from the University of Leeds, who began by saying simply, ‘The most boring of all arguments is that men are better than women’), I smiled and nodded my way down the page… until I reached the summary paragraph outlining the polarised reactions that Baselitz’s own works have caused. Or at least, that’s what it should have been about. What it was actually about was Baselitz himself, on the one hand regarded as a ‘walking monument of art history, one of the major figures of post-war art,’ and on the other as ‘self-aggrandising and publicity-seeking.’

Let’s be clear: I’m with Griselda Pollock, and find Baselitz’s comment boring, uncritical and stupid. But how do we deal with artists if we like their art and loathe their politics? And how do we draw a distinction between them and their work?

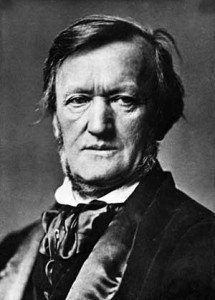

The straightforward answer – the answer that it is easiest to apply if the artist in question is safely dead – is that we should treat the two separately, but acknowledge that creative work is bound to be political in some way. Wagner is the obvious case-study: the majority of listeners, I would wager, have both a tremendous respect and love of his music, but would freely acknowledge his personal and political views to be far distant from their own. They would probably also be able to tell you what they loved about Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg and realise, without condoning it, the distasteful, anti-Semitic parodying in the character of Beckmesser and the determined, and now uncomfortable, nationalist statements that conclude the work. Wagner’s subsequent association with the Third Reich has blackened his reputation further, of course, and in Israel his music is still deeply controversial (a situation beautifully and eloquently discussed by Daniel Barenboim in his journal). But almost for this very reason, music-lovers are careful to state their position on the music, and then deal with the necessary caveats to clarify that loving the music does not equate to loving the man.

The straightforward answer – the answer that it is easiest to apply if the artist in question is safely dead – is that we should treat the two separately, but acknowledge that creative work is bound to be political in some way. Wagner is the obvious case-study: the majority of listeners, I would wager, have both a tremendous respect and love of his music, but would freely acknowledge his personal and political views to be far distant from their own. They would probably also be able to tell you what they loved about Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg and realise, without condoning it, the distasteful, anti-Semitic parodying in the character of Beckmesser and the determined, and now uncomfortable, nationalist statements that conclude the work. Wagner’s subsequent association with the Third Reich has blackened his reputation further, of course, and in Israel his music is still deeply controversial (a situation beautifully and eloquently discussed by Daniel Barenboim in his journal). But almost for this very reason, music-lovers are careful to state their position on the music, and then deal with the necessary caveats to clarify that loving the music does not equate to loving the man.

In less dramatic examples, performers and composers can be thoroughly unpleasant individuals but superb artists. These people are usually, to a certain extent, forgiven their behaviour away from the concert hall and operatic stage, since the greatness of their creative contributions is seen to outweigh the impact of their character flaws. Or, as Tommy Dorsey put it when told that a trumpet player had been suggested to him with the endorsement ‘he’s a nice guy’: ‘Nice guys are a dime a dozen! Get me a prick that can play!’

But what do we do now if an artist and public figure does or says something that is deeply upsetting, shameful, unacceptable, illegal? How much should that affect their artistic career? I don’t claim to offer any answers here, but I think it’s worth considering a few recent cases and their circumstances. For example:

At the launch of the Met’s 2013/4 season, Anna Netrebko and Valery Gergiev (both supporters of President Putin), were starring in a production of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin. There was an LGBT rally planned for the first night, a peaceful protest against the ban on LGBT competitors at the Sochi Winter Olympics, and which planned to make reference to Tchaikovsky’s own homosexuality. Peter Gelb refused to back the rally, stating that the Met doesn’t take stances on social and political issues.

In October of this year, there was an enormous protest outside the Met, as it staged John Adams’s The Death of Klinghoffer. The critical backlash went on for weeks, and the planned cinema broadcasts of the opera were cancelled. It seems the Met can’t avoid ‘taking a stance’ on social and political issues after all. The opera has been at the center of major controversies ever since its premiere in 1991 – in particular Alice Goodman, the librettist, found herself unemployable after the event. He career and reputation were in tatters after this work which some saw as ‘glamorising terrorism’.

Georgian soprano Tamar Iveri lost season contracts after being accused of making extreme homophobic comments on her Facebook page.

Film director Roman Polanski was arrested in 1977, charged with a host of crimes against two girls of 13 and 14 years old, including substance abuse and lewd and lascivious acts. He left the United States, where the charges were brought, hours before being sentenced in 1978 and has avoided extradition ever since. He has directed 15 films, starred in several more, and won an Oscar for Best Director (for The Pianist in 2002).

This is murky territory indeed, but that is all the more reason to look at it more closely. Clearly great talent is not an excuse for morally reprehensible actions. But how one draws the line is difficult: what is and isn’t acceptable for a public figure (which performers, writers, artists, etc. are now all considered to be – indeed, thanks to social media, anyone can be a public figure); whether people should be forgiven for making mistakes or bad judgements; whether a distasteful point of view should be enough to ruin a career. What are the social responsibilities of the artist? And what about their art? The two are inextricably linked – and yet, to some extent, separable. Just imagine: if anyone were ever able to prove that Walter Sickert was Jack the Ripper, would we judge his paintings differently because of it? And would we be right to do so?