And in English…

When I was still an undergraduate, I remember sitting with several of my fellow students discussing their recent holidays. One of them had been on a trip with their family to a country rich in ancient buildings, early signs of Christianity, and traces of times past. The guide leading them and the rest of the tour group had been conversant in several different languages… but not, alas, theirs. And so they stood outside one magnificent ruin after another, listening to him babbling away for several minutes in a tongue they couldn’t understand, until he would turn at last to them and say benevolently, ‘and in English: church.’

I was reminded of this recently as I began to explore the question of how English audiences, from about 1860 to the present day, have understood that most highly-prized of elite musical genres, the German Lied. Because simply put, from a linguistic perspective, a great many listeners don’t actually understand it at all. They listen, they follow the parallel translation in their programme, and afterwards they speak of its profound beauty, and how wonderful it is to let such inspired music simply wash over you.

I confess that such sentiments leave me in despair. Erlkönig is not supposed to be beautiful, it’s supposed to be terrifying. If Gretchen had just let it all wash over her, she would have been lazing on a deckchair sipping a piña colada and musing on Faust’s manly features, not frantically spinning in a dim little closet whilst her head spun and her heart exploded in her chest. But of course, if you add that magical element of linguistic distance, they can be doing whatever they like. If you don’t speak German, if you haven’t gone digging for the meaning, the very words themselves become wholly musical. Sounds of speech with the sounds of song and piano strings.

What is fascinating to me is how resistant most people seem to be to the idea of helping themselves with this. Or at least, they are now. From the late nineteenth century to the early twentieth (and yes, of course, the period around the world wars is particularly complex), you could buy yourself a very respectable edition of the Lieder of Schubert, Schumann, Mendelssohn, Brahms and others with a singable English translation. Don’t know your Dithyrambe from your Doppelgänger? Fear not! The likes of Reverend Troutbeck, Natalia Macfarren and Mrs Pierpont Morgan were on hand to save you the embarrassment. You could sing away to your heart’s content in your own language, and leave those fearsome clustered consonants to the professionals.

Such a practice has largely been forgotten. But I wonder if we’re really the better for it. Last week, I heard a completely magnificent performance, by Roderick Williams and Christopher Glynn, of Schubert’s Winterreise in a new English translation by wordsmith extraordinaire, Jeremy Sams. All three men stood to introduce the work before we heard it: to argue in favour of sung translations, the primacy of the story, the necessity for clear communication between artists and audience. I was already more than convinced, having heard Glynn and Toby Spence perform Sams’s English version of Die schöne Müllerin last year at the Oxford Lieder Festival. And this Winterreise was a profoundly effective and moving event, not to mention a masterful rendition. By the time we were settled into the second song, I had almost forgotten that it was ‘supposed’ to be in German at all. Even knowing the thing inside out and back to front auf Deutsch, there was not a jarring moment to be heard. Every familiar image was there, every sentiment and subtext as carefully painted as in Wilhelm Müller’s original texts. Where poetic necessity had forced a change, it was executed with such profound insight into the psyche of the winter traveller that it seemed wholly appropriate and natural. No wonder the performance received such an ovation – I can’t recommend it highly enough, and I suggest you book your tickets to its next outing, at the Wigmore Hall, as quickly as possible.

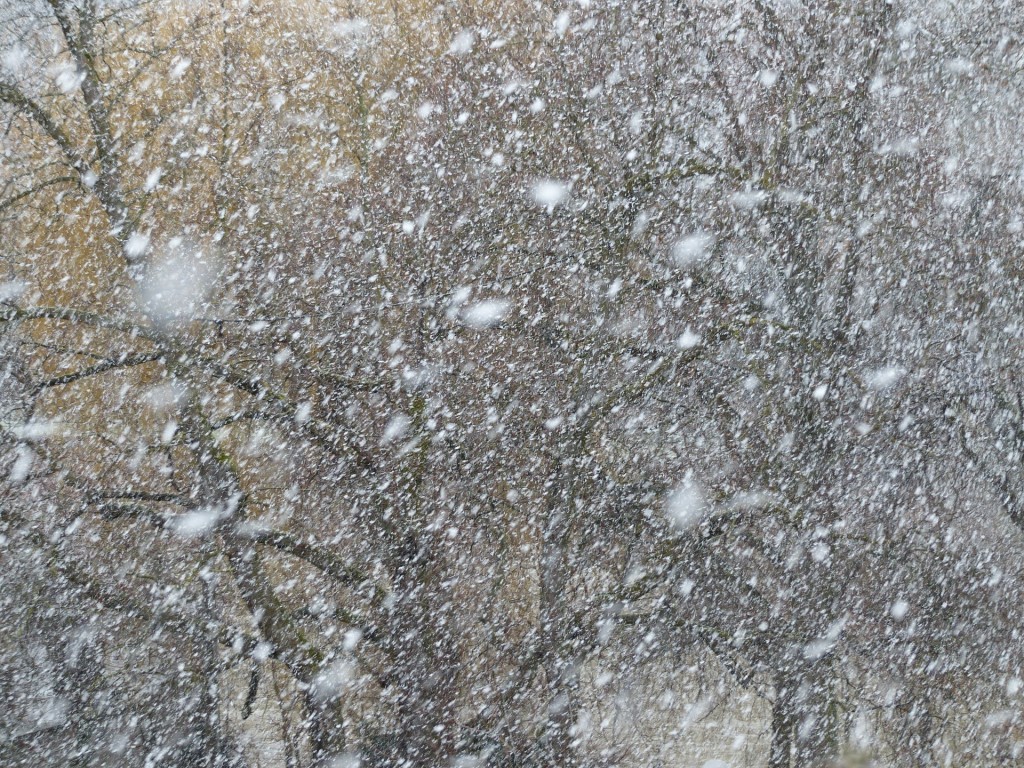

Having spent the last few months wading through translations of the past 150 years, there is something else it’s important to mention. The most common location in which we hear translated singing, of course, is the opera house. Opera translations come and go, are declared dated and funny and have to be ditched. Anyone looking at Lied translations – particularly those contemporary with the composers of the original songs – is also likely to find themselves chuckling at the sometimes biblical, sometimes childlike renditions of Great German Poetry into English. But on Jeremy Sams’s recommendation, after I started picking his brains about this a few months ago, I had a go at it myself. I sat down with the score of Erlkönig, and a pen, and a large pile of scrap paper. And to put it mildly, producing singable translations is bloody hard. After about four hours, a lot of talking to myself, and a pile of discarded rhymes that could have stocked the Christmas pantomime circuit for the next couple of years, I finally came up with something not entirely dreadful. It still needs work, and tweaking, and thinking about. But the real revelation was not, in fact, how difficult it was. (That much I had been able to predict.) Instead, it was how much more deeply I ended up engaging with the poetry and its protagonists as a result of trying to lead them from one language to another. I speak German. I know that song well. But I don’t think I’ve ever felt so strongly that I know the people in it as deeply as I do now. And that’s the trick, of course, of the great translator – which Sams certainly is – that you have to understand absolutely the characters before you, realise their every thought and feeling… and then get out of the way, so that these things can be shared with an audience. Parts of Winterreise are indeed beautiful. But if it just washes over you in German, try the translation. Then you’ll see it for what it really is, and feel it too: icicles down the spine, and storms in the head and heart. Better a blizzard in English than the decorous snowflakes of a language you don’t speak. They might be pretty, but they’ll melt into meaningless vowel sounds so fast, you’ll never see winter at all.

Excellent! Thank you for the interesting and amusing essay.

Good article. It always helps the effectiveness of a translation when the performers happen to be Messrs Williams and Glynn. Amazing communicators, both. I’ve always enjoyed Sams’ translations of Mozart operas and he did a fantastic Threepenny Opera for Donmar Warehouse. There is a real place for this, and while it is not so commonplace in Lieder at the moment, if anyone can convince us it will be these fine artists.

Gretchen with a piña colada – now that would be something! An amusing post. I am truly glad I had German at school: barrier free access to the Lied. If only I knew Russian to understand the beautiful versesoif Tchaikovsky’s songs!