Handmade

You may have noticed, on Thursday of this week, that the Google doodle celebrated the 117th birthday of one Ladislao José Biro – the man who brought us a writing implement so strong, durable and quick-drying that it has stood the test of time and even proved invaluable during the Second World War. A few years ago, I took enormous pleasure in reading Philip Hensher’s The Missing Ink and finding out a little about Biro, and the many other men and women who contributed to the development of a skill, an art, a creative tool on which the sun now appears to be setting: handwriting. Hensher’s praise of the act of handwriting is both witty and deeply moving, and prompted me to copy out (yes, by hand), the following lovely sentiment:

Don’t be in a rush. Why are you in a rush? Why don’t you have two minutes to write something down? Why is your pen dashing in that awful way over the paper? Whoever described, or thought of describing, their handwriting as executing so many w.p.m? Why can’t you breathe, and lift, and take a moment to enjoy this small sensuous act? Do you stuff food pointlessly in your mouth, hoping to get it over with as soon as possible? Or do you hope to enjoy it? Writing can be like that. Sometimes, all we have is two minutes to eat a sandwich or we aren’t going to get anything to eat until six. At other times – let’s hope at least once a day – we like to sit down in company, and take a little bit of time to chew and anticipate and sit afterwards. That would improve our lives, just as taking a moment to write something by hand, to ourselves, to friends, to our families, is always going to improve their lives and ours.’

But as the new term gets underway, there is a marked differentiation between the note-taking methods in my adult education classes, where biros and pencils abound, and those for undergrads, who often bring laptops or tablets instead.

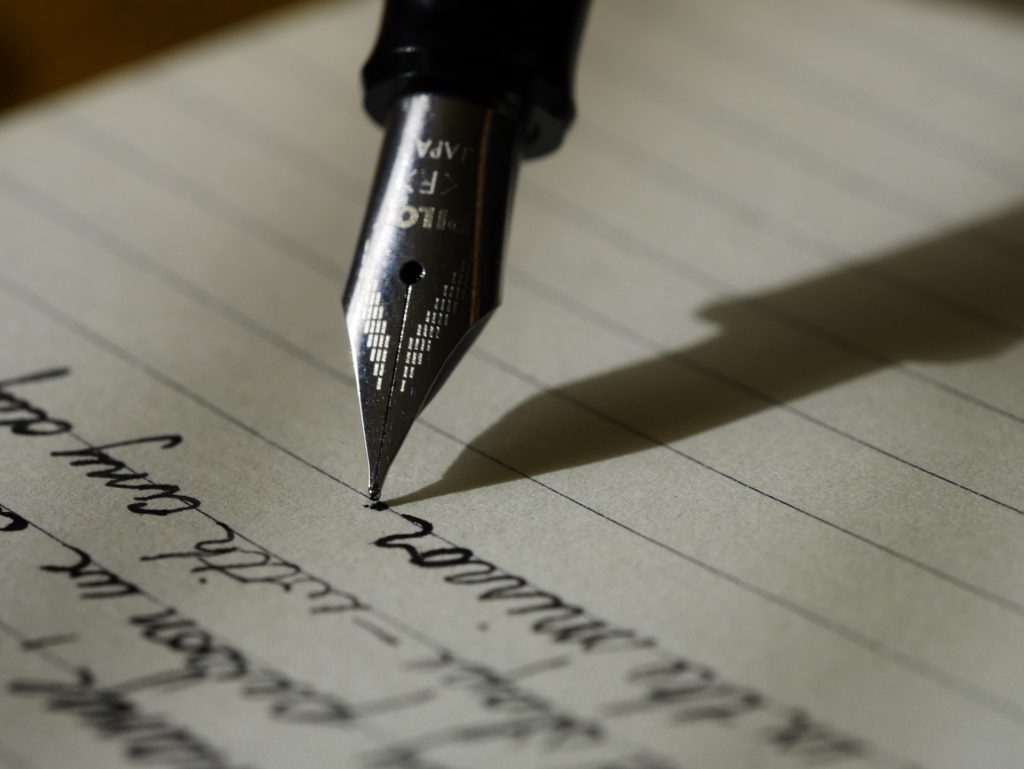

Of course part of me is nostalgic for the days of whole rooms of pen-wielding learners, because I spend an enormous amount of time hanging around collections of old things. Whenever possible I use a fountain pen. You wouldn’t catch me dead with a Kindle, for similar reasons of liking old, solid, real things. And generally, when people run out of inspiration for presents, the answer is usually notebooks, because I use them a lot. (Mind you, my writing is extremely tiny – excellent for the environment, not so good at getting through paper very fast.) However, there is more to my preference for penmanship than a wish for the aesthetic pleasure of good cursive script. Writing with a pen isn’t just about writing. It’s about making you think.

Simply put, we can’t write as fast as we can type. (Hence the invention of shorthand – something I have always been both curious, and too lazy, to learn.) So if you sit in a lecture and have your laptop with you, and someone starts saying something that sounds interesting/useful/quotable, you can probably type to keep up with them. But if you only have a humble pen and notepad, and your shorthand skills are as well-developed as mine, there’s no way you’re going to be able to stay with the speaker. Not a chance. Reception of the words and transferral onto the screen is not an option. You cannot be simply a vessel through which the speech passes. Oh no. You actually have to listen to it.

The same goes for taking minutes in meetings – always harder to knock them into shape if you typed in the meeting, because you’ll have written far too much and need to prune them if you don’t want to risk sending the committee members to sleep with the papers. And it also applies to books. This is a common problem for me. As a general rule, I will have a fixed amount of time at the British Library, and a list of things to research. So I will order the books in advance, gather them all at my desk, and start typing. I sit and read and type, working my way machine-like through the pile of books, and by the end of the day I will have far, far more information than I need, which I will then take home and process properly into CD, programme or lecture notes.

You might think that this method has its advantages. After all, I’m looking at a lot of stuff, and it may be something I write down on the off-chance will late join up with something else I’ve found, to make a previously unsuspected point very neatly. On very rare occasions, this does indeed happen. But for the most part, I read a lot, write a lot, and as I’m doing both of these things on a sort of superior level of automatic pilot, the rest of my brain develops strands and ideas and links between the stuff I’m mechanically typing out. So that when I get home and begin writing it up, the material is already semi-shaped by what I remember that train of thought being. And vast swathes of material I’ve written down are never looked at again.

As an undergraduate, I had a pen and a notepad for both lectures and essay research. It was hard work, and occasionally wrist-cramping… and I trusted my own critical faculties in a different kind of way. The paranoia of ‘I’ll just write this down, just in case…’ was not an option. I had to read carefully, listen attentively, and choose. No delayed process of trying to understand – it all had to happen in the here and now, brain switched to ‘pay attention’.

I’m not suggesting that it’s impossible to do this with a computer, but I think it changes the game considerably, and quite aside from the ever-increasing illegibility of peoples’ writing on the rare occasion that they are now required to put pen to paper, I think not having to handwrite so much makes it much harder for particular kinds of learners to grasp the basic skills of the precis and the ability – and courage – to choose what is important in a lecture for themselves. As a learner, I find it fantastically difficult to make myself engage with a PowerPoint presentation as something deep and thought-provoking, because it requires nothing more from me than to look, and perhaps copy and paste. If I want something to stick in my brain – anything to stick, from a lunch date to a musicological theory – I have to write it down. I have to touch it, feel the shaft of the pen and the rasp of the nib on the paper. Otherwise it’s not real. It’s just an ephemeral thing, and I’ll lose it again almost instantly.

Maybe that makes me an old dinosaur, but I rather suspect not. And after all, in a time when information is immediate, instantly available, and gone again in a swipe and a tap, I can’t help but think that it’s in schools and universities above all that we might help our students by occasionally suggesting they pick up the pen and find a way to be critical through the enforced slowness of that oh-so-durable bit of early twentieth-century technology.

By the way, did you know that Lewis Waterman patented his new and thoroughly modern fountain pen in the same year that the first machine gun was built? It was 1884. You probably ought to write that down…