Brave (old) worlds

Now that July has arrived, I’m about to have to start knuckling down to work again – to preparation for talks and notes for a whole host of wonderful things, including the Ryedale Festival, the Oxford Lieder Festival, the North Norfolk Music Festival and some forthcoming summer courses at City Lit. And yes, I am also still busily learning how to drive (third lesson this week, and no major cataclysms so far!). But I have enjoyed, for these last few weeks in June, a rare amount of space in my week to be allowed to get on with even more of an activity I can never seem to get enough of: reading.

Mostly, for pleasure, I read fiction. But just recently, and thanks to some excellent recommendations from friends, I’ve been widening my horizons and making my way through some non-fiction books. And as I always say, if you’re going to try something new, make sure it’s a friendly, approachable, manageable first step that you take. So I decided to read a book outlining the history of discoveries in quantum physics.

This was not quite as random and masochistic an act as it seemed. For one thing, the book in question was Lawrence M. Krauss’s The Greatest Story Ever Told… So Far, which is extremely readable, very engaging, doesn’t expect you to really know what the heck is happening when you start, includes many very helpful analogies and illustrations, and if all else fails includes a thorough an usable index so that you can go back to that bit where he first explained about gauge symmetries and try to wrap your brain around it again before carrying on. Actually, the difficult bit really is the wrapping-your-brain-around-it bit. All the words individually make sense, but sometimes trying to find any kind of means of conceiving or internally visualising this stuff is extremely tricky. Which Krauss freely admits, and does everything he can to help you with.

And for another thing, back in the dim and distant past as it might now be, I did in fact take Physics A-level (and Maths A-level, come to that), and we had a whole section on particle physics. We went on a study day to Bristol University about it and everything. Although mostly my memory of said study day is that much of it was way over our heads. Still, it was the first time I’d ever encountered Jammy Wagon Wheels. So not a complete loss.

The more I read, the more I remembered from A-levels. The more I remembered from A-levels, the more I remembered how exciting I’d found some of that stuff at the time, even though they were extremely hard work and rather stressful subjects at the time. Sometimes, Krauss’s book provided a historical context to things I’d known without any sense of when they were discovered (like the gradual conclusion, particle by particle, that an atom must contain electrons, protons, neutrons… and eventually, quarks). Sometimes, it elucidated things I’d never really understood the first time around. And I learned far more, as well, not least because of all the things we now know that we weren’t aware of – and certainly hadn’t made it to the A-level syllabus – in 1998.

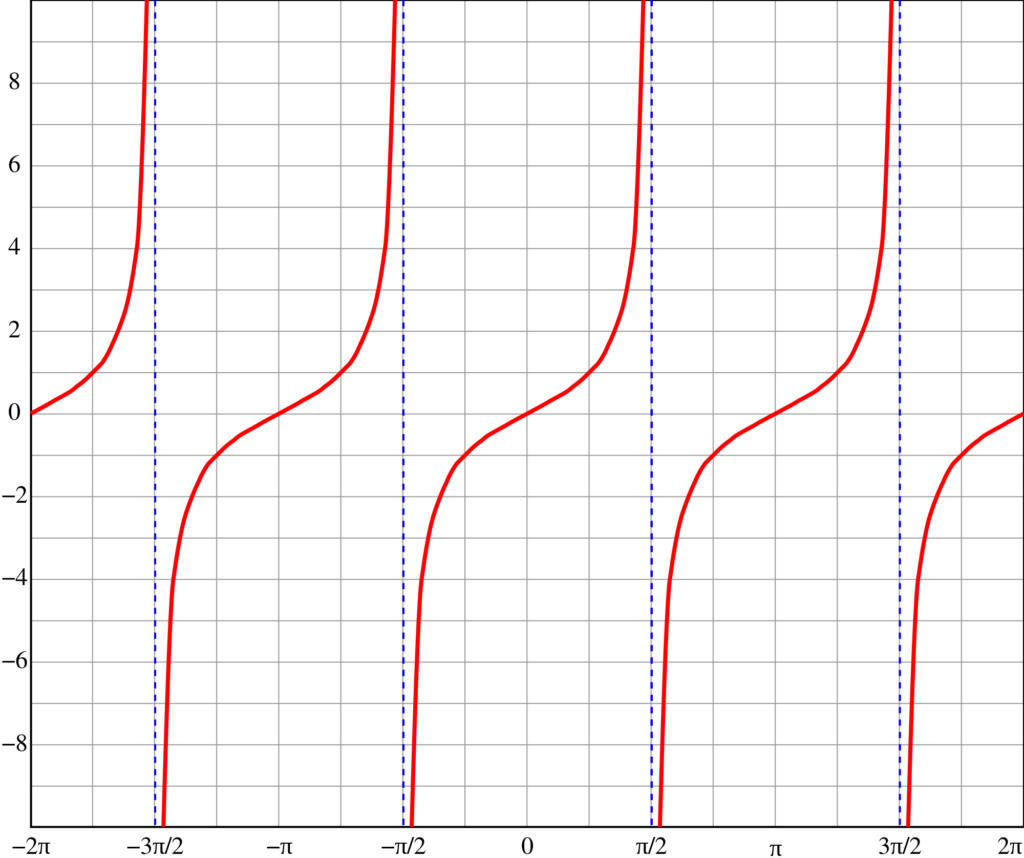

And sometimes, I found myself just stopping and marvelling at things that are considered fairly simple, basic features and concepts that I was able to appreciate for their brilliance and their beauty. One of my favourite things from Maths A-level, I now recall, was the asymptote – the graph (as for Tan, if you’re a trigonometry fan) where the curve never quite reaches the line… infinitely. Just think about that for a minute. This curved line will never get to the line. Ever. But it will keep getting closer to it, endlessly. Isn’t that amazing? Here it is:

If at this point you’re thinking that in fact, I’m an even bigger nerd than you thought previously, then I would happily agree with you. But I’m so, so delighted to have rediscovered these things, because I’d quite simply forgotten about them. I’d forgotten a lot of the theories, and certainly the maths. And when I was finding out about them last time, it was all geared towards an exam. Lots of exams, actually: six modules for Physics, four for Maths. January and July exams, equations to learn, graphs to memorise… and never quite enough time to sit back and really think about, absorb, unpack, picture, internalise what we were being told. I had wonderful school teachers who helped us all enormously, but even then, the exam system was panic-inducing (to me, anyway), and with Physics in particular, some of the concepts are just really brain-bending. Curved space? Particles that are also waves? Hell, even trying to get your head around what exactly happens when you flick on a light switch to make the bulb glow. It’s been an utter delight to find the time and space – and such a brilliant author guide – to come back to all these marvellous things.

If there’s a moral to this story, I suppose it’s twofold. The first is that reading about things that are new to you (or at least so lost in your distant history that they might as well be) can be really fun, fascinating and enriching. The second is that with the best will in the world, schools have targets, children sit exams, and sometimes there isn’t the mental space and time to really get to grips with these things before we get tested on them. The most terrible upshot of that can be a life-long hatred, phobia, panic and refusal to engage with any of those things ever again. And that’s a real tragedy, because as I discovered to my intense surprise and delight, something as simple as a curve still has the power to leave me utterly spellbound. I remember why I did those A-levels, and I want to know more again. And about other things, too: philosophy and biology, technological innovation and outer space. So come on, summer. There’s some serious reading to be done.