Music and the Darwinian dilemma

Let me tell you a fairy tale. It’s probably familiar. Once upon a time, there was a talented musician. Their family was almost certainly poor. When they were a small child, their parents noticed with astonishment that they could sing back entire complex melodies before they could even really walk. By the time they hit five years old, they were a prodigy – let’s say at the piano. They played, improvised, composed. They debuted in some impressive town, and made it big. When they were in their late teens or early twenties, they wrote something so amazing, so innovative and brilliant, that it was put on at once by the local orchestra. It was a hit. A rich prince guaranteed them an income. They spent the rest of their life composing stunning pieces, which have been performed ever since across the globe. They died young, probably of something a bit icky and probably leaving behind a rather complicated romantic situation. But their music lives on, and to this day, we hear their symphonies and sonatas in major concert venues performed by the greatest artists of the day.

In one of the weekly fascinating conversations I have with my wonderful students at City Lit, we got onto the question of why some music is more famous than some other music – and why some composers we hear more often than some other composers. It is quite easy to assume that the fairy tale I crafted for you – bits of which are relevant to quite a few of the composers we still do hear today – is basically how it went, and how these composers become The Greats. But I called it ‘fairy tale’ and not ‘biographical sketch’ for a reason.

Think of all the sub-characters I didn’t mention. The teachers. The piano sellers. The impresarios. The reviewers. Once the composer starts writing pieces, there’s also the question of the orchestral managers, the conductors, the concert hall and box office staff. Why should they programme this kid’s music? Who do they know? Who’s on their side? Will it sell? And reputations don’t get made on one performance, so that means persuading multiple orchestral managers, multiple conductors and concert halls. And then you need a publisher. Who keeps publishing you stuff. With a good circulation and reputation. With legal agreements in other countries so that copyright is assured and piracy minimised. With good publicity channels. On and on it goes. The web of individuals to make that prodigy into a superstar, and from a superstar into a Timeless Genius, is huge. And largely, we don’t really think about them.

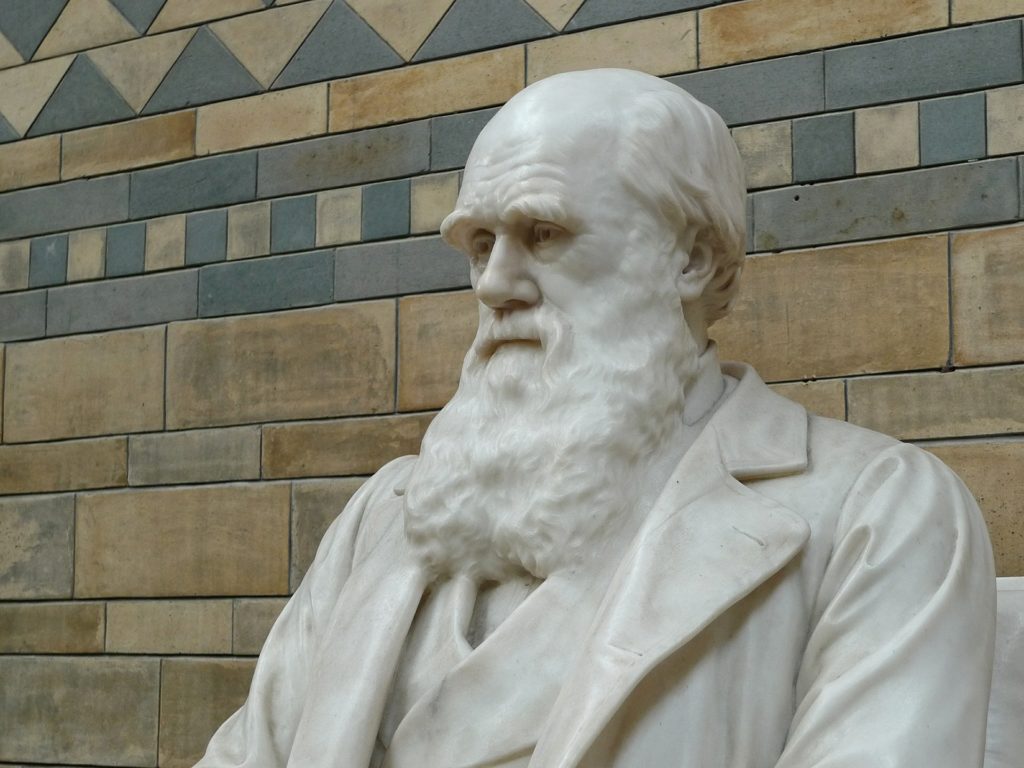

What we think about is the composer. Just the composer. In a neat appropriation of Darwinian theory, we imagine that only the composers who write things that are the perfect balance of innovative and comprehensible, brilliant and entertaining, forward-thinking and idiomatic, are the ones who survive. Forget the public at the time who scratched their heads and failed to understand it. Forget the shouty reviews from critics who simply weren’t brilliant enough to understand. Forget their terrible people skills, their fallings out with patrons, their commercial ineptitude. These people were brilliant composers, and that and only that is why we know who they are. In a beautiful, abstract space from which all the historical junk has been cleared away, they are the fittest, and they were destined to survive.

Actually, the truth of it is really more to do with the evolutionary network of all of the individuals in and around the composer. They – or let’s be honest, for the majority of the stories that resemble the fairy tale, he – has to write good music of course. But he might have written brilliant music but just never found a publisher to trust him. Or have struggled to get repeat performances of his music. Or have fallen out with the local patron. Or be told that she should be having children and getting married (or indeed pursuing his occupation as a gentleman without sullying himself with filthy commerce and selling his creations) and stopped at the front door… or made it out of the front door only to be laughed at by concert managers and orchestral managers because women don’t do that sort of thing. It’s not a level playing field. It was never really a meritocracy. It’s just far easier to believe it is.

Don’t get me wrong: we all do this because we’re used to thinking that way. We are told, when we listen to the radio or study the violin or piano or flute that we’re hearing and playing the good stuff. You don’t put dross in an art gallery, so you don’t make a brand new recording of bad tunes. The reality, of course, is far more complicated – and far more interesting – than that. The reality is full of people we’ve forgotten and who, hopefully, we’ll have the pleasure of rediscovering. Our tastes change over time. Certain composers are championed, or we are reminded of them, every now and then. The emphases in concert programmes shift. The radio presenters and recording companies seek out new things for us to hear and explore.

Brahms, Haydn, Beethoven, Debussy… they’re all great composers, no arguing with that. They’re also not the only great composers, not necessarily universally great composers (everyone has bad days); and they all, one way or another, got lucky into the bargain. Raise a glass to Darwin, please – a man of astonishing brilliance and insight. But be upstanding also for the many, many other people we never consider. The publishers, the concert planners, the impresarios who helped our favourite composers. And the composers who got no such help, and wrote wonderful music anyway. What a joy it is to find them now and then.

A thought provoking and encouraging piece, Katy. As ever. Thanks!