Childish things

On Thursday morning this week, I woke up to a horror familiar to many. I had run out of things to read. Having spent the previous couple of days attracting curious and mistrustful glances on London transport as I shook and wept with laughter through Francis Plug. How to be a Public Author, I had a whole day left before I got home again, and no book. Disaster.

Thankfully I was staying in the house of a dear friend which is absolutely crammed with books, so the next dilemma was how to choose something without spending so long nosing through the shelves that I ended up missing my train. The thing I eventually left with was not a weighty nineteenth-century novel, nor a brand new tome. It was, instead, Ian Seraillier’s The Silver Sword.

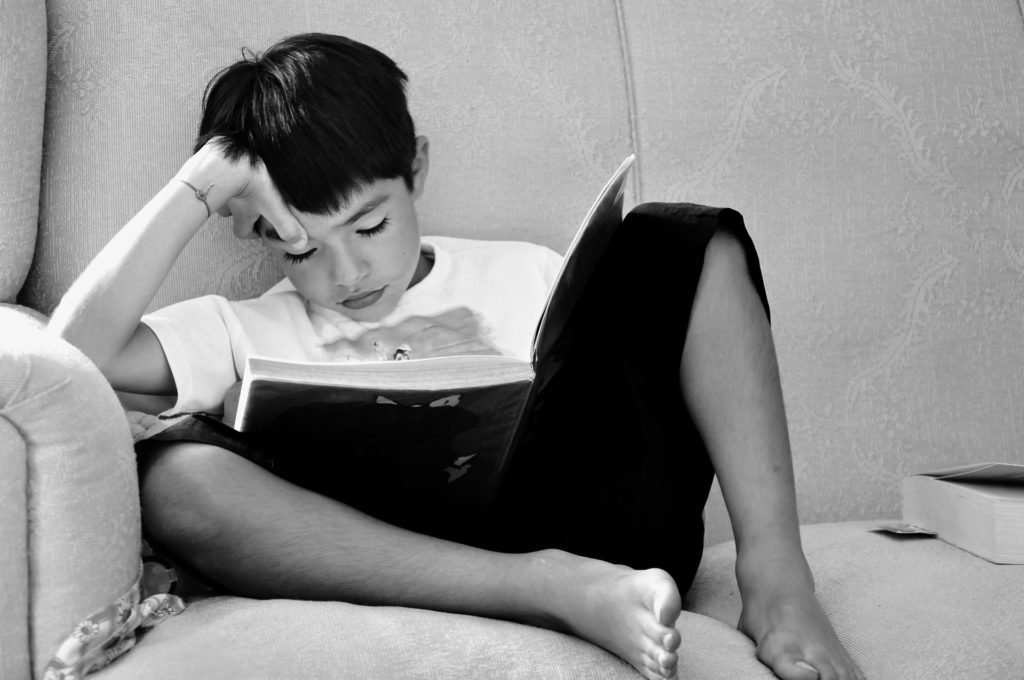

I have memories of being read this book, probably aged about 6 or 7, by our teacher at primary school. And of buying it, and reading it again, and adoring it. But that was quite a few decades ago now. What does it mean to revisit these lost stories of childhood?

Well, I was hooked. I was hooked, and I kept thinking, ‘isn’t he called…?’ ‘isn’t this the bit where…?’ as hazy memories of this gripping and deeply moving story started surfacing in my brain, the tale of a Polish family separated from each other by the Second World War, who fight to find their way back to each other in Switzerland via concentration and labour camps, periods in bombed-out buildings, and above all the tough journey of the children across hundreds of miles with only each other – and the wonderful kindness of strangers – to get them there. The stakes are high, and they feel intensely real. I was a mess by the end of it, I can tell you.

But the other real joy of revisiting The Silver Sword was to have some sense of where it – the book – was actually from. Six-year-olds not being particularly concerned with publication dates, I had no idea that Ian Seraillier had first published the book in 1956. I had no idea that he had been a schoolteacher, writing the book across five summers (it is less than 200 pages long) between his work and spending time with his family. And the research that he undertook for the novel is also rather incredible: poring over UNESCO documents, Red Cross records (the children in the novel all had real-life equivalents, in some cases with far unhappier fates), newspaper articles. The author’s daughter, Jane Serraillier Grossfeld, has provided a wonderful Afterword detailing her father’s efforts in making this a story of real people and things, even if the precise scenario is his own. And in reflecting about the book’s enduring popularity, she points to the fact that this was a decisive turning point in children’s literature and television (it was first televised in 1957) because it was an honest depiction of the horrors of war both on children, and intended for children. The BBC received many complaints to the effect that exposing such a young audience to the brutalities of the Second World War in this story was completely unacceptable. But none of the complainants were children.

There is much that could be said here about the importance of trusting audiences – and particularly young audiences – with difficult things and giving them the opportunity to decide how they feel about it. There is also nothing to stop adults having conversations with children about what they have seen, and what their thoughts are (in my experience, these are the most interesting conversations of all). I have no memory of being remotely traumatised by The Silver Sword at the time, though I do remember finding it very exciting, heart-in-mouth drama… similarly, I remember realising, not long afterwards, that if I was watching a familiar film and knew something bad was going to happen, I could just switch it off. I adored Willie Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, but Charlie letting him down by drinking the Fizzy Lifting Drink used to do me in, and the VHS was quite frequently left just before that scene started. Still, I knew what the trade-off was: if I could force my way through that betrayal and Charlie’s subsequent apology, I would be rewarded with Mr Wonka taking the gift that Charlie offered him and muttering, ‘So shines a good deed in a weary world.’ Which made it all worth it. Even if I had absolutely no idea that Mr Wonka was quoting The Merchant of Venice.

The best conversations between artists (of all kinds) and children happen when each party takes the other seriously, and trusts them with important, exciting, potentially difficult things. It is as true in The Silver Sword as it is in the outputs of Roald Dahl, C.S. Lewis, Jenny Nimmo and many other great writers of books for children and young adult fiction. And the care that is put into creating such stories is not to be underestimated – the research that must be undertaken, the personal experiences that shape the language and conversation, and the absolutely profound importance of these stories and why they are being written. Authors don’t write for no reason, and they don’t, if they are any good, write about nothing. We tell stories to share ideas, imagine alternative futures or pasts, and if we are very lucky they teach us lessons about history, or the present, or ourselves, or each other. That is the case regardless of the age of the intended reader.

Ian Seraillier heads The Silver Sword with a quotation from Michael Tippett’s A Child of Our Time: ‘Here is no final grieving, but an abiding hope. / The moving waters renew the earth. It is spring.’ At the end of her Afterword, Jane Serraillier Grossfeld recalls that when her father spoke about his book to school children, he ended with a photograph from the UNESCO publication Children of Europe. It is of a boy, crowded amongst others, brow dirty and scarred, face creased in unhappiness. Of which Seraillier said simply, ‘No child should ever again have that expression on his face.’

I loved this.