Strictly business?

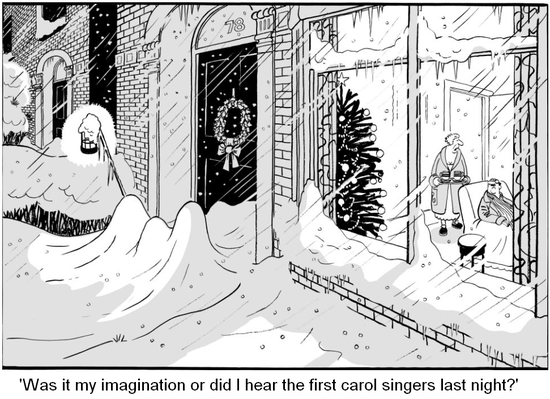

Well, it’s most definitely That Time Of Year again, as evidenced by the glitzy-to-laughable arrays of Christmas lights sprawled across high streets, and the impossibility of avoiding Little Drummer Boy and Calypso Carol even when doing your weekly food shop. Santa is polishing his sleigh as I type this – and for many of my singing friends, that means carols. Lots and lots of carols. Endless evenings of candles, cassocks and O come all ye faithful, with the odd smattering of Messiahs in wigs and breeches. Catch them any time after the middle of the month, and they’re liable to start twitching at the mention of Bethlehem.

Of course, it’s not just professional choristers who are taking the time to brush up their gold, frankincense and myrrh. Hundreds of amateurs singers – choral societies, church choirs, and groups of good friends with a love of music – are also busy learning appropriate Handelian choruses and tramping the streets bringing tidings of great comfort and joy. That’s most certainly something to encourage, and you only have to spend a little time wandering through London’s St Pancras Station, past the three old pianos which reside in the main concourse, to see how much live music-making still means to a wonderfully broad array of people.

But there’s a difficulty, and it particularly concerns singers. There are, on any given day, plenty of calls for singers needed to come and bump up choral performances, carol services and so on, spread across Facebook, Twitter, and various ‘Dep List’ and ‘Singers in [insert name of city]’ websites. For those professional singers who make their living from such work, it is crucial that organisations and fixers are encouraged to pay a decent fee – an acknowledgement of their time and training, their standard and the quality of their performance. Organisations such as Equity have, quite rightly been working hard to ensure that singers are not expected to undertake long rehearsals and concerts for woefully small sums of money. Unfortunately for these campaigners, there are also a number of amateur singers who are quite prepared to work for little or no fee to do the same gigs, and thus undercut the pros. This makes it far harder to enforce a fair wage for the professionals, as fixers are aware that in most cases they can find a willing dep at half the price.

The professionalization of musical performance – certainly on the scale with which we are familiar – is really only a nineteenth-century invention. As more and more music colleges, conservatoires and specialist schools began to appear, the number of performers and composers who received institutional training (and in more recent times, high-level qualifications) increased exponentially. However, the 1800s was also a time of very high-quality amateur musicianship, with many middle or upper-class businessmen and their wives taking music lessons, and performing with friends and acquaintances in their own homes for pleasure. This meant that ‘professional’ orchestras and opera companies might include (or rely upon help from) amateur musicians in addition to those who made a living from their musical skills. (And if you want to know more, and are stuck for Christmas present ideas, you can find a more detailed outline of all of this in my co-edited book Brahms in the Home and the Concert Hall, which came out this September… ok, plug over.)

The professionalization of musical performance – certainly on the scale with which we are familiar – is really only a nineteenth-century invention. As more and more music colleges, conservatoires and specialist schools began to appear, the number of performers and composers who received institutional training (and in more recent times, high-level qualifications) increased exponentially. However, the 1800s was also a time of very high-quality amateur musicianship, with many middle or upper-class businessmen and their wives taking music lessons, and performing with friends and acquaintances in their own homes for pleasure. This meant that ‘professional’ orchestras and opera companies might include (or rely upon help from) amateur musicians in addition to those who made a living from their musical skills. (And if you want to know more, and are stuck for Christmas present ideas, you can find a more detailed outline of all of this in my co-edited book Brahms in the Home and the Concert Hall, which came out this September… ok, plug over.)

As recorded music took the place of domestic live music-making, and society was shaken and restructured in the wake of two world wars, the gap between professional and amateur musicians began to widen. This is not to say that the amateurs got ‘worse’ and the professionals ‘better’ – more that the opportunities for each group gradually came to be more clearly delineated. Amateur violinists are not called upon to pitch up and fill in for ill colleagues in the BBC Symphony Orchestra, for example. The choral scene is a bit more complicated because of very large-scale choirs being mostly amateur (The Bach Choir, for instance); but groups such as The Sixteen, Philharmonia Voices and the BBC Singers are professional groups. And so are the core choirs at a significant number of churches, particularly in larger cities.

Add to all of this the current financial climate, the sheer number of Christmas musical events that takes place across the UK, and the fact that many fairly decent singers who were choral scholars once upon a time and are now lawyers or accountants who enjoy the opportunity to sing with a high-standard ensemble, and the problems start to emerge. The work of Equity, the MU and other similar organisations is vital to get potential employers away from the ‘it’s good experience, of course you should do it for nothing’ mindset that still predominates in some places. But that also requires the advocacy of those talented amateurs who would like to continue to perform.

So: if you are a professional singer, and organisations are offering unreasonably low fees for work, you should speak to Equity (the singer’s union) or another organisation with your interests at heart, and find a way to negotiate, if possible, with your would-be employers. And if you are an amateur singer, keep singing! It’s brilliant that you’re out there, and that you love it so much. ‘Amateur’ should NEVER be a dirty word, and it is the enthusiasm and passion of people like you that gives us such a brilliantly rich musical culture. But make sure that any work you take on is not at the expense – literal and metaphorical – of your professional colleagues. Support them, and make it clear that you will only accept certain fees on the understanding that you are not a full-time pro. If we can develop an environment in which professionals and amateurs can work in harmony together, in a variety of musical settings, we’ll all enjoy a much happier Christmas.