Who’s listening to opera? Part One

Some thoughts on opera, funding, and finding audiences…

At the end of a week where the game of two halves rather lost its equal opportunities for both sides, newspaper and online debate has produced a raft of articles concerning a slightly different kind of inequality. When the 2015-18 Arts Council funding was announced at the beginning of July, it was revealed that 58 organisations will be losing their place in the national portfolio altogether; and that funding for English National Opera would be slashed a mighty 29%, from £17m to £12m.

The allotting of Arts Council monies is always a hotly debated subject, with commentators passionately advocating the need to support grass roots cultural endeavours; the importance of spreading the money across the UK rather than simply focussing spending on the capital; and of course, interviews with those organsations who stand to lose out, to discover how they are going to cope with the loss of support and the impact on their public profile, as well as their bank balance.

So the reaction of ENO to the serious drop in their own funding was of particular interest. There were no complaints, no acrimonious statements – just a calm acceptance of their fate, and the determination to make clear that Sir Peter Bazalgette, previously the ENO chairman before taking over the Arts Council at the end of last year, had not been involved in the deliberations. John Berry, ENO’s artistic director, calmly announced that the organisation needed ‘to develop a new business plan which recognises the challenging funding climate’, whilst maintaining artistic excellence and an international reputation, and ensuring that ENO did not strain its ‘cost to the public purse.’

Following this extraordinary stoicism, theatre critic Michael Billington is not impressed. ‘Where’s the shock and outrage?’, he wrote yesterday. ‘Why is the Arts Council punishing ENO for innovation and imagination?’ With the likes of Calixto Bieito’s production of Carmen (and more recently, Fidelio) and Phelim McDermott’s production of Satyagraha – not to mention Terry Gilliam’s Benvenuto Cellini – ENO has proven itself to be a daring and inventive house prepared to take risks. And that, Billington observes, is what we should be supporting, even if it does not lead to packed houses for every show: ‘… a theatre devoted to artistic adventure is bound to risk occasional box-office failure: it was precisely to buttress such eventualities that the subsidy-principle was established.’

So what should the balance be? To what extent should a large organisation which requires significant public subsidy be required to demonstrate that it has broad popular appeal? ENO have taken the decision to include music theatre productions in their forthcoming seasons as a means of boosting ticket sales, and this has met with as much applause as it has dismay. It’s not as if the (crudely put) culture vs. capitalism debate is a new one: musicians in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries traded the protection and potential tyranny of the noble patron for an increasingly free market economy, and one can hardly blame the likes of Beethoven, Brahms, Dvořák, Schumann and many other household names for seeking to appeal to ‘the public’ as well as the musical connoisseurs. Touched with genius or not, musicians need just as much to eat, pay rent, buy clothes, and deal with day-to-day existence just like anyone else (as Virginia Woolf so eloquently observes in A Room of One’s Own). The trick, so brilliantly pulled off by the best of these composers and performers, was to find a way to make money and retain artistic integrity. Think of Brahms’s Liebeslieder-Walzer; or Schumann’s Kinderszenen; of the countless Schubert Lieder which would delight an amateur as much as a consummate professional, or the piano duet arrangements of Liszt’s symphonic poems.

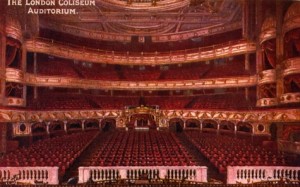

For an institution like an opera house, this becomes a different kind of challenge. How does one continue to include Don Carlos and Die Walküre in the repertoire without being accused of privileging long, difficult works without broad appeal? The answer is two-fold: music, and trust. Trust first, and in both directions. The opera house must trust its audience to engage with a wide range of productions (something that ENO excels at when it comes to the innovative and unusual). It must not apologise for what it does, either – some operas are long and don’t have happy endings, and you know what? That’s fine. It never stopped Carmen, Don Giovanni or La Bohème from being hits. The audience must trust the opera house, and feel as if it is neither being patronised through ill-conceived updates ‘to make the opera more accessible’ nor expected to deal with directorial navel-gazing. Finally, above everything else, music. People go to the opera, hum tunes to the opera, recognise excerpts of the opera without any awareness of the plot, because the music gets under our skin. That is just as true of music theatre, by the way. So all I can say is: good luck to ENO. They are evidently willing to go on fighting. Let’s all take a moment to remind them what they’re fighting for.

***

Keep an eye on the site… Part Two is on its way soon!