Amateur bravery

They say you learn something new every day – and as a professional researcher, I can confirm that this is definitely the case. But we’re not professionals all the time, and I want to tell you this week about something I learned in a context entirely removed from my work. It made me think very hard about my own life and career, and gave me massive new-found respect for a lot of people I’ve been fortunate enough to meet over the years. It made me realise just how hard it is to be an amateur.

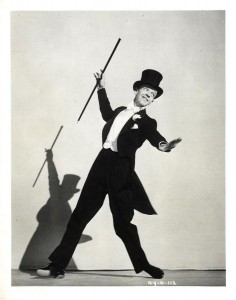

Last month, after years of idly toying with the idea and never doing anything about it, I started tap-dancing lessons. I adore Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly: the music, the movement, the shiny shoes… and finally a friend of mine convinced me to just sign up and have a go, with the promise that she’d come along to be my learning buddy. And so we joined a beginners’ class, an hour’s lesson late on a weekday evening.

Last month, after years of idly toying with the idea and never doing anything about it, I started tap-dancing lessons. I adore Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly: the music, the movement, the shiny shoes… and finally a friend of mine convinced me to just sign up and have a go, with the promise that she’d come along to be my learning buddy. And so we joined a beginners’ class, an hour’s lesson late on a weekday evening.

All was going swimmingly until the teacher found himself unable to continue. It was a shame – he was a calm, gentle, thoughtful person who took time with each of us as we stumbled and stamped across the floorboards, and found comfortable slow swing tunes to keep us occupied. When he left a new, younger tutor turned up. His first session was fast-moving, tougher, to pacier music (but not swing, alas). I wasn’t entirely convinced, but I was prepared to go along with it. Nothing ventured, nothing gained, right? And it isn’t like I’m a stranger to challenges, or committing to learning new things.

This week, he gave his second lesson. He taught us a long, complicated routine which most people in the room couldn’t do. He let us rush. He counted us in slowly but didn’t keep us in time – everybody panicked and sped up, causing yet more frustration. He tried to teach us through repetition, without giving us the space to let it sink in. Heck, he was forgetting how some of it went, and he’s a professional dancer. The rest of us had come along after a day of work, probably mostly doing something completely different from tap-dancing… and then endured an hour being discouraged and disheartened.

At the end of the session, my friend gently steered me into the pub next door and sat me down. As the lesson had gone on, I had found myself getting more and more upset, and as I sat there weeping into my beer, I monologued my way through my thought process during the class (thankfully my friend is extraordinarily patient and kind, and just let me do so). It went something like this. I am not stupid. I am a professional researcher and musician. I can count to four, and I have a good sense of rhythm. I want to learn. I am prepared to be corrected. I automatically accord teachers great respect and want to do my best for them. But I have been made to feel that I have failed, because of bad teaching, and yet unable to respond or complain, because of the nagging feeling that it might well be me doing it wrong… I’m not a dancer, after all, so it must be my fault, mustn’t it?

As I was talking my way through my grievances, I had a sudden blinding flash of revelation. I thought back to a group of people who each and every year had given of their money and time to leave their homes and jobs, and come and learn about something that was far from their professional arenas. They had worked extremely hard, and made themselves incredibly vulnerable by putting themselves publicly in a situation that made clear their lack of expertise. In return, they had asked only for guidance, empathy and understanding. They had come because they wanted to be there. They were the students who each August attended a week-long music summer school, for singers, pianists, conductors and composers, in Shrewsbury.

From 1998 to 2012, I too had been involved in this summer school. It had started life in Hereford, and I had first joined it as a teenager, attending a young musicians’ piano course. As the years passed I had graduated up the ranks and ended up as the Music Director by the time that funds, alas, ran dry two years ago. In that time, I gradually came to realise that the majority of attendees were not, as I was, aiming for a musical career. They left their professional personas at the door. When I became senior enough to be granted access to the database of attendees, I discovered that my fellow students included university professors, lawyers, senior businessmen and women, charity workers, doctors and school teachers. But for that week, they were all learners, and they were indulging their passion: music. They did it because they loved it, and it meant an enormous amount to them. They were not stupid. Many were often frustrated, and I rapidly lost count of the number of times that people hit crisis point midweek, doubting their abilities or the validity of their attendance. Given the quality of tuition they received, in some cases it would have been equivalent to me, after four tap lessons, being told to run a routine in front of Michael Flatley and then work through his feedback. Yet they came so far, and did themselves proud time and time again – they had the extraordinary courage to stand up in front of a room full of strangers, and say: this is me. This is a thing that means a great deal to me, and I’m going to do it as well as I possibly can. I’m not a professional, and it doesn’t matter. What matters is that I’m trying.

As I let myself be comforted after my tap lesson, I realised that what I was feeling was exactly akin to these brave amateurs I was lucky enough to meet every year at summer school. I now knew what it was to be in their shoes (even if mine were more Fred Astaire than Frédéric Chopin) – something I’m not sure it’s possible to appreciate fully unless you’ve actually been there yourself. To say it was humbling would be a serious understatement.

So the next time you find yourself using the word ‘amateur’ in a perjorative sense, just think about what you are saying. The word means ‘to love’, and the amateurs I’ve met, in the dance class as well as the summer school, really do love what they are doing – why would they bother, otherwise? And for those of you teaching amateurs, in whatever area: please remember that the people in front of you are putting tremendous trust in you. They are seeking to learn a skill that is probably quite distant from their actual profession, and they are relying on you to help them. Just because they can’t instantly do it, doesn’t mean they are stupid or untalented – they are pushing themselves beyond their comfort zone on purpose. Be kind. In our age of high-level professionalization across all subjects, the amateur is a rare and courageous individual. And our culture is all the better for the people who try new things with enthusiasm, and with love.