Creative labours, artistic myths

One upsettingly warm evening this week (autumn has apparently not got the memo yet), as I was collapsed in front of the TV, I found myself watching a re-run of that wonderful magic and mystery show, Jonathan Creek. Faked suicides, walking through walls, missing paintings… I love this kind of stuff, not least because I enjoy getting unreasonably competitive about trying to work it all out before the big reveal. And, Holmes-like, in one of the first episodes of the series, Jonathan himself spells out the central tenet of all magic, equally applicable to the improbably complex scenarios in which he often finds himself: ‘We mustn’t confuse what’s impossible with what’s implausible. Just about everything I dream up for a living relies on stuff that’s highly implausible. That’s what makes it so hard to work out: no one thinks you’d go to that much trouble to fool your audience.’

There are many situations in the creative world where such ‘fooling’ is not exactly intentional, but the familiarity of a given set of circumstances has led us to forget, ignore, or otherwise overlook the amount of ‘trouble’ is gone to in the pursuit of an artistic ideal. How many operatic performances have you sat through in which you’ve carefully considered the number of personnel involved, the hours it would have taken to plan and create set, costumes and props, the blocking and lighting – not to mention the hours, weeks, months, years of training of the singers, musicians, dancers and everyone else involved? Probably not very many, because the point is usually to put these Olympian efforts at the disposal of music and narrative, to beguile us into watching the action unfold as a real and true thing.

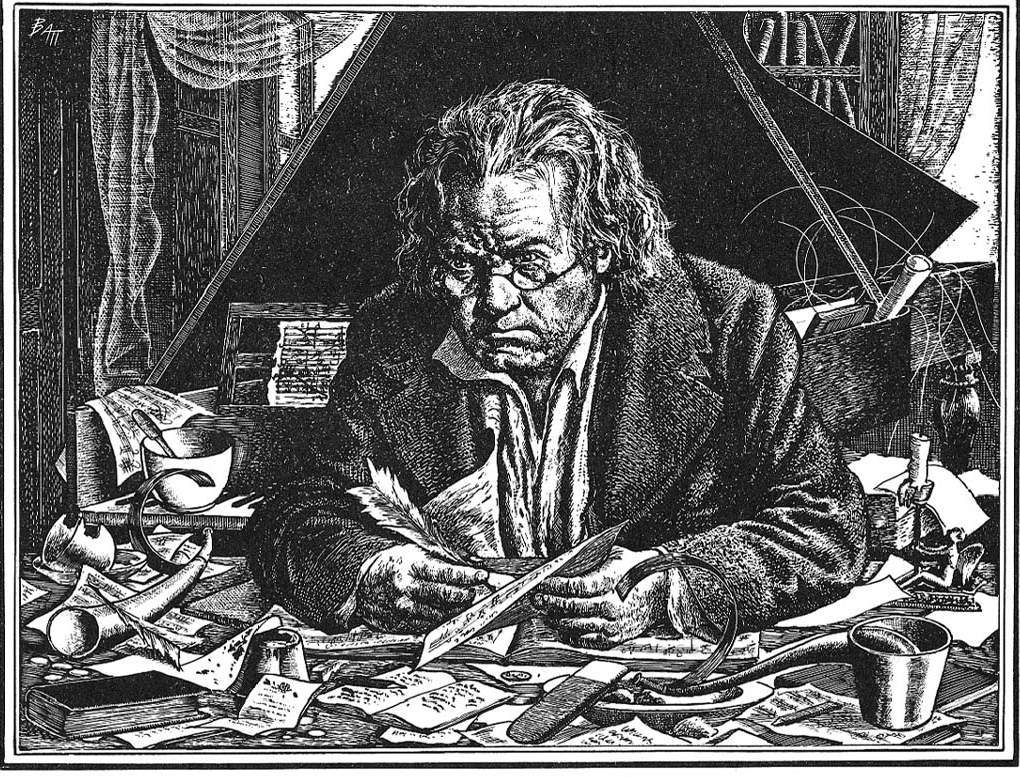

And of course, someone has to write the opera. Now picture this scene. (Which should be easy, because I’ve lost count of how many times it’s shown up in various films and TV shows.) Creative genius sits at desk. Much hair-tearing. Either the real or implied passing of a great deal of time, because it’s night, or his (it’s usually a man) bottle of wine is now empty, or making friends with other empties. Smudged inky fingers, a wastepaper basket – or, in extreme cases of creative virtuosity, the floor – overflowing with crumpled balls of paper. Maybe we see him chucking a few over his shoulder, or at the maid. And then finally, finally… inspiration! He seizes his quill (or other poetic writing instrument of choice), scratches furiously across the paper, leaps to his feet in triumph with the completed document clutched in his fist. The white heat of inspiration, a work of brilliance born… in some rare cases, this may indeed reflect reality. But often it becomes shorthand for the long, careful, exhausting planning of new compositions, discussions with performers or librettists or other possible collaborators, the restrictions of a particular commission… the list goes on.

I could do this all day. How much work and thought and planning has to go into even producing ten minutes of live radio broadcast? An hour of television? A Hollywood blockbuster? Or we could look in other creative directions – there is a fantastic new blog post on the Metropolitan Museum’s new Assyria to Iberia exhibition in which one of the team talks about the process of just getting the exhibits into the building (which includes knocking down a wall, because it makes access easier). As someone who has planned tiny, temporary exhibitions including only exhibits kept within the organisation, let me tell you that selecting items, constructing an overall narrative, writing captions, determining layout and space, sorting environmental and security arrangements and so on, takes far more time and care than you might think. And for poets, novelists and writers of non-fiction, countless drafts and missing details, proofing and checking, reordering and revising is the norm.

We are fantastically lucky to have such amazing creative happenings available to us. Every film, play, opera, concert, exhibition, poetry reading, novel, biography represents an enormous commitment (sometimes of a great many people) in order to bring it to fruition. In some cases, these creations are designed to disguise or distract from the frantic paddling that has gone on to set the swan in motion. In others, the evidence is there but we may be prone to overlook it, somehow working on the basis that so commonplace a thing as a one-room art exhibition, or a new paperback, can’t be all that major an undertaking if there are already so many of them out there.

I would like to propose a different view. The sheer number of cultural artefacts that surround us (and here I include live events as well as physical objects or recordings) are a testament to the incredible importance of creativity, imagination, and the inquiring mind in our society. Their prevalence is miraculous, when you consider the back-breaking work that goes into their creation. At a time when every penny is being counted, and every arts organisation must justify itself as having a purpose beyond ‘just’ producing artworks (as recently argued by the artistic director of the Unicorn Theatre), let us remember this. And let us value the fact that we ‘go to that much trouble’, as Jonathan puts it. We underestimate the importance of such a fundamental human activity at our peril.

Totally agreed. Creativity is such a unique gift that takes such a toll on the performer that it should not be underestimated and cannot be fully appreciated. This blog resonates on so many levels..