Playing hard is working hard in the music business

This week, I’ve mostly been thinking about virtuosos. As I was putting together my notes for a lecture on Paganini, Chopin and Liszt, and the transformation of the solo musician’s role in the first few decades of the nineteenth century, everything from repertoire choices and touring schedules to notions of physical agility and artistic responsibility have been swirling around in my brain. And it has brought two particular ideas to the surface.

The first idea, which I’ve seen in print more than once, and most recently in Thomas Gould’s piece for The Guardian on his multi-faceted musical career (for which, by the way, I heartily applaud him – he is a very fine player), is that all great soloists prior to the present era were one-trick ponies. In Gould’s article, he writes that ‘violinists such as Paganini and Joachim’ were busy ‘touring concert halls with a handful of iconic concertos and recital programmes. But the music world today has changed… today’s listeners have broad musical tastes across diverse musical genres,’ and musicians are bored of playing the same old thing, and thus ‘trying to do things that haven’t been done before.’

Let’s set the record straight here. Both Paganini and Joachim were orchestral musicians as well as soloists. They also performed a vast amount of chamber music (with Joachim running several string quartets, in Germany and England). They both composed, arranged, and published in a range of different genres – chamber, solo, orchestral. Paganini was a master improviser and produced a number of arrangements and pot-pourris of the most popular operatic numbers of his time, because he knew they would have mass public appeal. Which was also why he bothered to tour Italy, Austria, France and England in an age before trains, let alone planes and automobiles. And he deliberately didn’t write much of his solo lines down, in case someone else figured out how he was able to play complete pieces on one string, how scordatura tuning enabled him to play notes that the violin ‘shouldn’t have been able to play, and so on. Oh, and Joachim conducted the first British performance of Brahms’s First Symphony, in Cambridge in 1877.

These musicians were multi-talented in the truest sense of the word. They didn’t just learn three concertos and set off on a mission for world domination – they also performed in numerous concerts in which they were one participant among many (the word ‘recital’, to describe a solo concert, was introduced after Paganini had died, let’s not forget). They played and wrote what they hoped would be popular, particularly in Paganini’s case. Chopin and Liszt wrote operatic paraphrases too, with the demand for Liszt to perform his best-loved works being so extreme that he was criticised in the press for yielding to popular demand and playing his paraphrases rather than advertised programmes of more ‘serious’ music. He also got into trouble for improvising and elaborating pre-existing compositions and not giving due deference to the composer’s written score (as did Paganini – who rather cheekily claimed that such elaborations were merely the ‘Italian style’). I’m all for performers remaining flexible in their careers now, and variety is the spice of life for musicians and listeners, of course, forging links and suggesting possible connections to new approaches and genres. But this isn’t new! And if we forgot it for a while, it was never entirely lost – just partially white-washed by musicological and marketing approaches that needed us to think about certain musicians in certain very separate, distinctive ways.

The second point is one of physicality. In an age where the physical, bodily presence of people is becoming weirdly irrelevant in certain scenarios (you don’t need to be in the same room as a person or object to interact with it now, after all – and recordings have been disembodying performers for decades) and yet utterly obsessive in others, like sport and fashion, the notion of musician-as-athlete often gets lost. Yet physical control and flexibility is what makes great musicians able to pull off virtuosic performances. Like Liszt accompanying Joachim in the finale of the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto, a lit cigar between the second and third fingers of his right hand. Or Alfredo Campoli whizzing through gypsy melodies with left-hand pizzicato and bowed notes at the same time. And for singers, this is also crucial, even if the physical exertions of hard-as-steel diaphragms and larynxes are concealed beneath concert gear or operatic costumes. One of my favourite moments of any reality-TV fame show was the episode of Any Dream Will Do in which the final four would-be Josephs were taken to the set of Les Misérables and asked to perform the barricade scene. They all slumped in the stalls, brimming with relaxed self-assurance, grinning at the professional cast as they watched it unfold – running around the stage, shooting guns, climbing up the barricade, waving the French flag and launching into ‘Do you hear the people sing?’. When it came to their turn, the fittest of the four made it through about a line and a half of the song before they collapsed in a panting heap. People have to be extremely fit to perform. But because this great athleticism is supposed to seem effortless, because opera is not weight-lifting and it has been decided that we in the audience must remain blissfully unaware of the physicality of performance, there are plenty of stories of singers continuing to perform in agonising pain, or being refused the chance to have the audience made aware if they are suffering from some kind of illness that could affect the quality of their singing or their stamina.

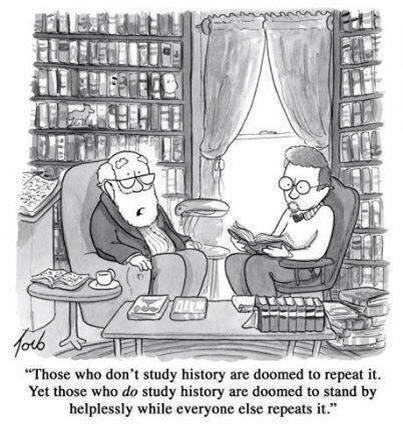

I’ve spoken elsewhere about the centrality of myth-making to music of various kinds, and these myths can be as destructive as they might be useful. What is absolutely crucial is that we remember that they are just myths, and go looking for the facts and details. The course that music history has taken was not inevitable; big-name musicians did not all just perform three pieces on repeat until the 1960s; the solo concert was not the standard means of performance until a little over a hundred years ago; performers can’t be performers unless they train, work exceptionally hard, build huge physical resilience and think aesthetically and historically too. There’s no business like show business. And we who enjoy the fruits of those labours, and are privileged to witness those many-layered careers, would do well to remember that.