Why we shouldn’t trust Those People

How dearly we love to categorise. Whether it’s heading to an event you found under the “Classical music” section of an events guide, steering offspring away from the “Supernatural Fiction” young adult section in the book shop, or shouting at the checkout staff because the eggs weren’t in the “Baking” aisle in the supermarket, the things in our lives are most often neatly divided into labelled boxes for our ease and enjoyment.

The extent to which this shapes and determines our everyday existence is considerable. But more than this, the categories of Things (objects, events, artworks and so on) have come to carry such strong cultural significance that we end up categorising the People who engage with those Things along similar lines. And that is very dangerous indeed.

It is most pressingly, physically dangerous if Those People bear a label which positions them on the national or international stage as objects of fear or anger – Migrant, for example, or perhaps Socialist. But more insidious, lower-level (and usually less violently handled) divisions also exist. Certainly in the arts, and certainly in music. And in the last couple of days alone, four particular instances have come to my attention – in which Those People are variously women, young people, black Americans, and a group classified by the writer as “luvvies”, by which I think he means lovers of the theatre and those with more left-leaning politics than his own.

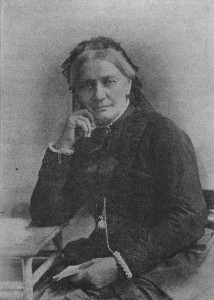

Let’s start with women. This was the work of Damian Thompson, reporting in The Spectator on Jessy McCabe’s excellent achievement of successfully petitioning Edexcel to include, at long last, some female composers on their A-level syllabus. Although Damian doesn’t think it’s excellent at all – rather he spends several hundred words explaining why no female composers, living or dead, are any good, with a healthy dash of factual inaccuracy thrown in to strengthen his case. (There was an outstanding response to this by Emily Hogstad – I recommend reading it immediately after you’ve cast your eyes over Damian’s article in order to fix your blood pressure.) This is an outstanding double-whammy: all women composers are bad, and all people who rate women composers (who I suspect mostly consist, in Damian’s brain anyway, of other women) have no musical or critical faculties.

Let’s start with women. This was the work of Damian Thompson, reporting in The Spectator on Jessy McCabe’s excellent achievement of successfully petitioning Edexcel to include, at long last, some female composers on their A-level syllabus. Although Damian doesn’t think it’s excellent at all – rather he spends several hundred words explaining why no female composers, living or dead, are any good, with a healthy dash of factual inaccuracy thrown in to strengthen his case. (There was an outstanding response to this by Emily Hogstad – I recommend reading it immediately after you’ve cast your eyes over Damian’s article in order to fix your blood pressure.) This is an outstanding double-whammy: all women composers are bad, and all people who rate women composers (who I suspect mostly consist, in Damian’s brain anyway, of other women) have no musical or critical faculties.

Let’s stick with The Spectator for our second example – the luvvies. They are, apparently, the only people who will have enjoyed J.B. Priestley ‘s An Inspector Calls, screened last Sunday. James Delingpole believes Priestley ‘s play to be “poisonous, revisionist propaganda”, “a load of manipulative, hysterical tosh”. Which is an impressively decisive view for someone who freely admits, as James later does, that he’s never read the play, or encountered the work at all before finding it on BBC1. (Between this, and Damian’s little slip about Clara Schumann only being taken seriously as a composer because of her surname, even though the pieces he cites were written before she married Robert, I do worry about that magazine’s recruiting policy…) By the end of this dyspeptic rant, we are in no doubt at all who we need to blame for the celebration of this play which James considers such rubbish: actors, bleeding-heart liberals, luvvies, anyone who ever studied the play at school, the “celebrity purveyors of cast-iron bollocks” who encourage people to explore the play, and of course Priestley himself for being a “national treasure” who had the temerity to think that capitalism might not in fact be the answer to everything. Once you’ve dismissed Those People, you’ll realise who can tell you how it really was: “serious historians” and, of course, James.

Such articles as these two Spectator pieces are ulcer-inducing for their shouty and unsavoury perspectives; but Those People at fault in the eyes of their authors, in each case, are not necessarily spelled out clearly as I have indicated above. The only thing worse than feeling furious at reading some of these things is also feeling defensive, because you are among the implicitly judged groups of people they mention, rather than those explicitly undermined. The situation becomes even worse if assumptions about Those People are made kindly, with a seemingly positive intention: such as Rupert Christiansen praising the social media initiatives of opera houses because it can reach “a constituency resistant to opera’s charms, the young”; or Norman Lebrecht’s embarrassing decision to entitle a brief message from Morris Robson “Classical music ain’t dead, brother. Its just weepin…”, because obviously that’s how to best relate the point Morris was making (namely that we shouldn’t make sweeping generalisations about the classical music listener demographic). Nice work, boys. Stereotypes well and truly reinforced.

Last year, I was at a wonderful discussion session at King’s Place which featured Nuria Schoenberg-Nono, Alexander Goehr, John Deathridge, Nicholas Snowman and Tom Service. As Tom turned to Schoenberg-Nono to ask her about the ways in which audiences were increasingly prepared to explore this taxing Modernist music that her father had written, she stopped him. We always do this, she said – we start by erecting a difficult obstacle called “Modernism” like it’s a bad thing, a thing to be overcome. Why can’t we just call it music and talk about it like that? Why do we have to isolate it, and the people who like, play, listen to or understand it?

It’s a tricky thing to do – we are all steeped in the art of categorisation, of Things and of People, all the time. But isn’t it worth a try? And by the way, if you read this post and wondered why I referred to all of them men by their first names, and women by their surnames, it was an entirely deliberate attempt to reflect countless music history texts I’ve read which do the same, to differentiate Those People. Did it feel weird to you? Because it certainly did to me, when I typed it. Maybe it’s worth thinking about that, too.

Damian Thompson does not compose his Spectator headlines. The points he makes in his article are banal but true. There has been no great female composer, though there have been many great female instrumentalists and singers. The twitterati who are trying to work up a storm of righteous indignation (as with Sir Tim Hunt, their juiciest victim) could clinch their case by naming a single great piece of classical music by a woman. But where is the female Grieg or Chopin or Bruch?

The problem is far more complex than you suggest. I could easily name several excellent pieces of music by women: Alice Mary Smith’s Symphony in A minor, Fanny Mendelssohn’s Piano Trio, any of a number of songs by Josefine Lang, Cathy Berberian’s “Stripsody”, several pieces by Judith Weir. But there are several tangled wires going on here at the same time. How are you defining ‘great’? How much of an allowance are you prepared to make that the social context within which women composed until most of the way through the last century was severely restricted and amenable neither to writing in large musical genres (often those considered to be most ‘important’ in a composer’s output) nor to having the kind of public profile that a male composer might have enjoyed – including, for example, the right to conduct his own works? Are we only counting something as having a right to be ‘great’ if everyone has already heard of it? (Which seems to be your point – I wonder how the Schubert pioneers of the nineteenth century would feel about that.) Writing one enduring piece of music is not the same as being a ‘great’ composer, whatever we mean by it, so conflating the two is pointless. I’d also be fascinated to know what prompted you to choose the three composers whose names you then mention.

“Priestley himself for being a “national treasure” who had the temerity to think that capitalism might not in fact be the answer to everything.”

That isn’t Priestley’s problem, nor does Delingpole suggest it is. His problem is that he suggests capitalism is the answer to nothing at all; indeed, that it is inherently bad; and that the Edwardian era consisted mainly of toffs in top hats going about destroying the lives of “the lower orders” for the hell of it. All this is, in the expressive language of Delingpole, bollocks; capitalism isn’t perfect, but it contains good than bad, and is a damn sight better than the alternatives.

For whatever it’s worth (given you attack Delingpole’s lack of long-term connection with the play), I was made to read and watch the damn thing at the age of 16 for GCSE English.