How does it go, again?

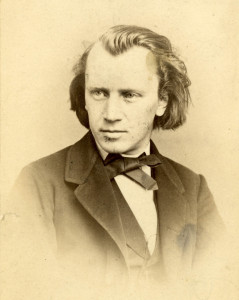

The sun is shining, the blossom is out… and as the Easter holidays pitch into view, I have just finished my script for another ‘Building a Library’ on Radio 3, which I’ll be recording in a couple of weeks. For those who heard my slot last year (or indeed anyone who’s spent much time on this site), I’m sure you won’t be surprised to hear that the piece in question is by Brahms – this time, his Violin Sonata in G major op.78. And as with last year’s assignment, the whole process has been fascinating.

In 2015, new at this game and starstruck by the shiny piles of unexplored CDs before me, I ended up writing a post here about the importance of careful listening. This time – and I felt this more and more intensely with each passing recording – my attention became increasingly focussed on the score. I’d printed out a copy of the first edition of Brahms’s Sonata (thanks to IMSLP) and was sitting, through each rendition, with the printout on my lap and a pencil in my hand, scribbling away in the hope of sketching in some of the details distinctive to the duo playing. It was, I thought, a piece I knew pretty well: it’s one of my favourite works by Brahms, and also a piece I’ve played on several occasions, with different violinists. But the more I looked, and the more I listened, the more I realised that actually, there was heaps of information on the score that I hadn’t noticed. Weird information. Information which actually contradicted a great many of the things that you would expect to do at a given point in the work. Information which, it had to be said, a number of my recording artists also appeared not to have seen.

Like the route to the station we walk every day, the drive to school to drop off and pick up the kids, the train line we know like the backs of our hands, after a while, we stop looking at familiar things. We don’t see the details around us unless they are suddenly, shockingly different: a wall collapses and blocks the road, or a bright ‘for sale’ sign appears by the pavement. So it can be, too, with familiar pieces of music – and let’s be honest, there is a great deal of repertoire being programmed so often in classical concerts that it’s hard not to keep hearing it, even though this is a less prevalent practice than it used to be. It’s pretty likely that we’ll be familiar, if we attend concerts or listen to music regularly, with at least one piece on every programme we hear.

The privilege of producing an episode of ‘Building a Library’ is that, given the opportunity to access so many recordings of a work you think you know, you come to realise you don’t really know it at all. Or at least, the comfy, familiar shape of your favourite performances have blinded you to the other possibilities the score offers. And sometimes, they blind you to the score itself, because you have merrily trusted that the people who get as far as making CDs to automatically Play it Exactly Right. Which is not, in fact, the case. They might aim to do everything on the score; or they might not have the same score you have; or they might not be aiming to do everything on the score; or they might not hold the score to be as privileged a document as their colleagues do and deliberately mess around with it a bit. That’s their decision – they are the interpreters. And we should remember that, just as we should remember that editing a score itself is an act of interpretation. Also we should remember that interpretative trends, in both cases, change with time.

The privilege of producing an episode of ‘Building a Library’ is that, given the opportunity to access so many recordings of a work you think you know, you come to realise you don’t really know it at all. Or at least, the comfy, familiar shape of your favourite performances have blinded you to the other possibilities the score offers. And sometimes, they blind you to the score itself, because you have merrily trusted that the people who get as far as making CDs to automatically Play it Exactly Right. Which is not, in fact, the case. They might aim to do everything on the score; or they might not have the same score you have; or they might not be aiming to do everything on the score; or they might not hold the score to be as privileged a document as their colleagues do and deliberately mess around with it a bit. That’s their decision – they are the interpreters. And we should remember that, just as we should remember that editing a score itself is an act of interpretation. Also we should remember that interpretative trends, in both cases, change with time.

I confess that personally, I’m rather fond of starting with the aim of trying to do what the composer asked. All of it. Obviously on previous attempts to master this particular sonata in performance, I didn’t manage that – but when I try again, I’ll have a much better sense now of what I’m trying to achieve. And the matter seemed somehow more pressing in this case because the performance markings are unexpected. How It Goes does not, according to Brahms, quite tally with How It Goes according to quite a lot of artists who have recorded the piece. That is not to say that many of those recordings are not extremely interesting in their own right – and in some cases, supremely convincing. But they aren’t – as far as such things can be pinned down – actually what Brahms wrote. Does this still make the outcome we hear a violin sonata by Brahms? Well, yes and no. It is the product of Brahms and the performers. That is the case in every performance, from the superlative to the execrable, given of the piece in question. What changes, then, is levels of input from composers and performers. We can’t, after all, have one without the other, even if they are to be found in the same person. Isn’t that amazing? When you really think about it… there is no musical piece that is not in some way an artistic communication between someone prioritising composition, and someone prioritising performance. That’s the real magic of it. It’s why making shows like this is so much fun, and so endlessly fascinating. So now you’ll have to tune in on 2 April to find out: did I choose the closest adherents to Brahms’s score… or not?

***

Katy’s Building a Library will be broadcast on Saturday 2 April – check the Radio 3 website for details.

Katy, I am really looking forward to hearing this! Even the first bar has so much to provoke thought: just what is “Vivace ma non troppo”, for instance – I tend to think most performances lean more towards something-ma-non-troppo rather than “Vivace”… but these 6/4 movements with quite fast tempo markings (this and the Third Symphony, at least) seem to encourage something that’s broader than I (at least) imagine it to be. And the m[ezza] v[oce] marking is another that doesn’t always seem to come across. And why are the piano chords marked “dolce” but not the tune? Crikey – there’s such a lot here. I don’t envy you, but I do envy us hearing what you end up deciding and choosing. It’s certainly a “problem” piece as far as finding performances that seem to get close to what JBr. appears to have wanted, insofar as we can determine that from the notation. Incidentally, I assume you’ve seen the album leaf of the slow movement in Kurt Hofmann’s collection (probably from February 1879)? It’s headed “Adagio espressivo” which raises at least one interesting question. Link to it from this page: http://brahms-institut.de/web/bihl_digital/jb_werkekatalog/op_078.html

Many thanks, Nigel! Yes indeed, I had seen the ‘Adagio espressivo’ album leaf… yet another fascinating source in a web of remarkable and, as you say, strange and unusual performance directions. So much to say about it, and so little time… but I hope you enjoy the show when it airs!

Yes, ‘How does it go again?’ This was something I found myself asking years and years ago about a piece I had written as a student composer. Not only familiarity but also assumptions and preconceptions can shape how people ‘perform’: http://charleslines.blogspot.co.uk/2014/01/see-what-is-in-front-of-you.html