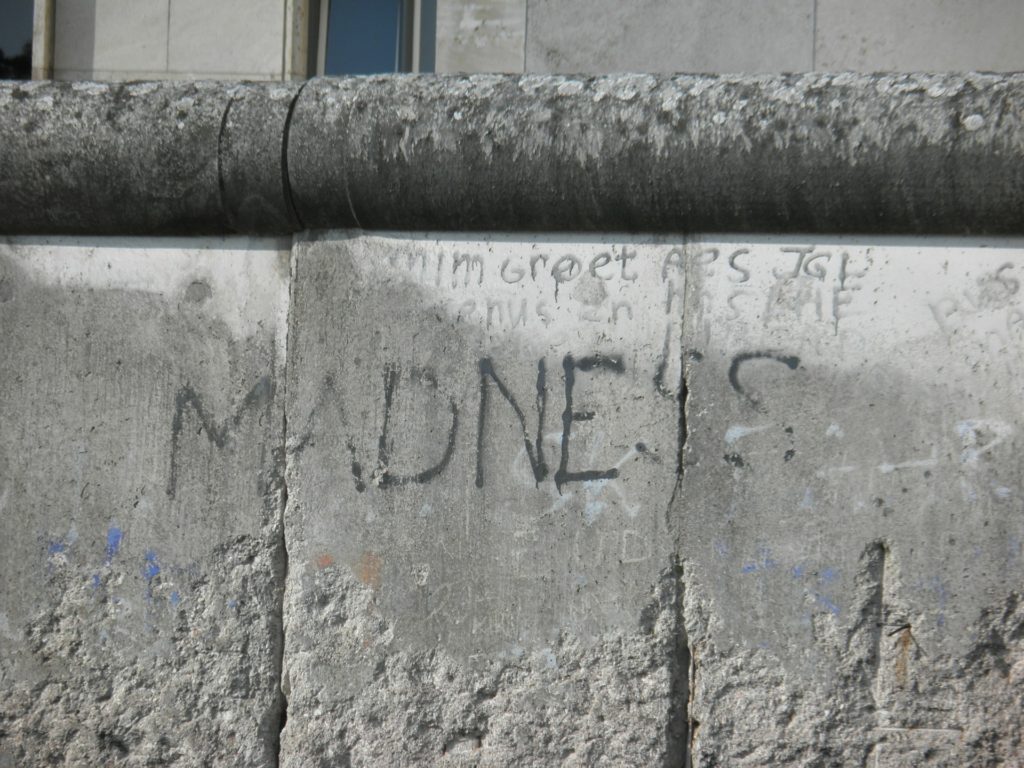

Creative truth at the edge of reason

Those of you who follow me on Twitter might have seen a particularly effusive tweet I posted on Friday evening, after a stunning evening of music at the Wigmore Hall given by Alice Coote and Julius Drake. It bore the title, ‘I myself am the enemy who must be loved? What then?’ and the programme consisted of three pieces: Schumann’s Kerner-Lieder Op.35, From the Diary of Virginia Woolf by the American composer Dominick Argento, and the world premiere of Nico Muhly’s Strange Productions, settings of poetry by John Clare and excerpts from G. Mackenzie Bacon’s On the Writings of the Insane. Which, you might think, seems like a slightly frightening prospect – three works concerned with insanity and mental illness, in which either poet or composer have suffered from demons in their minds. What state would we all be in by the end of it? How would we, and the performers, cope with such a soul-searching line-up?

The short answer is that it was absolutely amazing: exhausting and raw, yes, but also heartbreakingly beautiful and, in places, astonishingly kind. There is no such thing as ‘the music of madness’, it is not definable for the simple reason that ‘madness’ is a million different things, can exist in myriad colours and intensities, and can find its expression in similarly enormous range of manifestations. As Alice Coote wrote in her introduction to the programme, ‘Great artists and creators are no more immune to ‘illness of the mind’ than any of us. Their means of expression is simply more sophisticated… It seems self expression, creativity and sharing such creation are essential to our being. Perhaps the Arts are more vital to our mental health than we acknowledge?’

And as I sat there before the lights dimmed, reading through the texts that Muhly had chosen to set and listening to my neighbours giggling as they did the same and saying things like, ‘this is really barmy, though, isn’t it?’, I felt extremely lucky to be there and also rather sad. How many songs, and song cycles, and operas, and instrumental pieces, are concerned with the emotional fragility of their protagonists? How many characters wander into the unknown, the terrifying, the sense of rudderless movement through space? Dozens. The miller boy and the winter traveller of Schubert; the poet of Dichterliebe, for all that it doesn’t result in his death; Berlioz’s heartsick artist in Symphonie Fantastique and Lélio. There are more opera characters than I can possibly list here, too – either those who fall to pieces and remain there, like Tom Rakewell or Lucia, or those who are brought to a single act of mad rage, like Canio. And yet these pieces are established in the repertoire, their emotional impact somehow softened by their long-accepted, canonic status. Like looking at a piece of beautiful, intricate furniture that has been smoothed over the years by layers and layers of polish.

Try explaining the plot of Lucia di Lammermoor to someone who has never seen or heard it before. Try explaining Die schöne Müllerin or Winterreise. I’ve written elsewhere about the reactions of some of my undergraduates to such high Romantic temperaments (everyone gets dumped, don’t they? Can’t these people just get drunk and get over it like the rest of us?). We know, really, what an awful and soul-wrenching series of events make up the plots of The Rake’s Progress, I Puritani and Pagliacci – of Carmen, too. And yet audiences can get terribly uncomfortable when they are made to look this squarely in the eye when they go to hear the work live. No wonder Peter Maxwell Davies decided to pull no punches, not a single one, in Eight Songs for a Mad King. There is nowhere to hide from what unfolds in front of us there.

And with that as a mental backdrop, the Muhly and Argento of Friday night took on an even more extraordinary hue. Strange Productions is thoughtful, beautiful, kind to its speakers: it doesn’t shy away from the sense of helplessness, hopelessness, stuttering uncertainty and unanchored living that is inherent in its texts, but it seeks neither to ridicule nor to paint in blackest angularity the ways in which they think and write. It is not frightening, though it is unbearable in its message. From the Diary of Virginia Woolf changes its shape and tone as the diary entries themselves go past, from the nightmarish to the heartbroken, and the desperate attempts in her final diary entry of March 1941 to fix herself firmly in the mundane, just as we hear the rest of reality gently collapsing around her.

How can you not hear Schumann differently after that? The Kerner-Lieder date from 1840, before things started to go badly wrong for him, although swings from high nervous energy to dizzyingly deep melancholy were already a part of his life. And in the penultimate song, Kerner and Schumann ask: ‘Who made you so ill?’ – the answer is man, causer of mortal wounds, destroyer of peace. These writers and composers want us to listen and feel, regardless of the plush surroundings of a concert hall or opera house, regardless of the nice clothes you decided to wear out for your evening of culture, regardless of the sweet little ice creams at the interval and the glossy programmes. What matters, to them, is the people. The emotions, the words, the music. It is pure, and moving, and often terrifying or heart-breaking, but if we don’t try to be open to it – all of it – then why are we there? Swear to listen, and be brave about it. And, whilst you’re about it, you can also swear to help those who are suffering from mental illness. It is inherent in us all, and closer to us than we ever imagine.