Let’s Play 6: On pondering the Proms

No, don’t worry, this is not a post about Rule, Britannia! or Land of Hope and Glory. Plenty of other people have already written, posted, tweeted, shouted or sat pensively on the fence about that particular chestnut. This is, in fact, a post about singing.

If, like me, you watched the First Night of the Proms on BBC 2 on Friday – or indeed listened on Radio 3, or caught up with the thing after the fact – you’ll know that the programme brought together the inevitable Beethoven (the ‘Eroica’ Symphony) with a world premiere by Hannah Kendall called Tuxedo: Vasco ‘de’ Gama, Aaron Copland’s Quiet City, and Eric Whitacre‘s Sleep. I could have done very nicely without the frankly vapid ramblings that preceded Kendall’s piece in favour of the composer herself actually getting to tell us a bit more about the inspiration and background of the piece, which was wonderful; and Quiet City brought a lump to the throat thanks to the exquisite playing of the BBC Symphony Orchestra and in particular the two soloists in this piece, cor anglais player Alison Teale, and Philip Cobb on the trumpet. That all this was achieved with a socially-distanced ensemble, Sakari Oramo at the helm, in a space with all the acoustic subtlety of St Pancras station – don’t forget they were approximately 6,000 people down on the usual leavening effect of having an audience – was nothing short of miraculous, and I sincerely hope the sound engineers were bought many celebratory drinks afterwards.

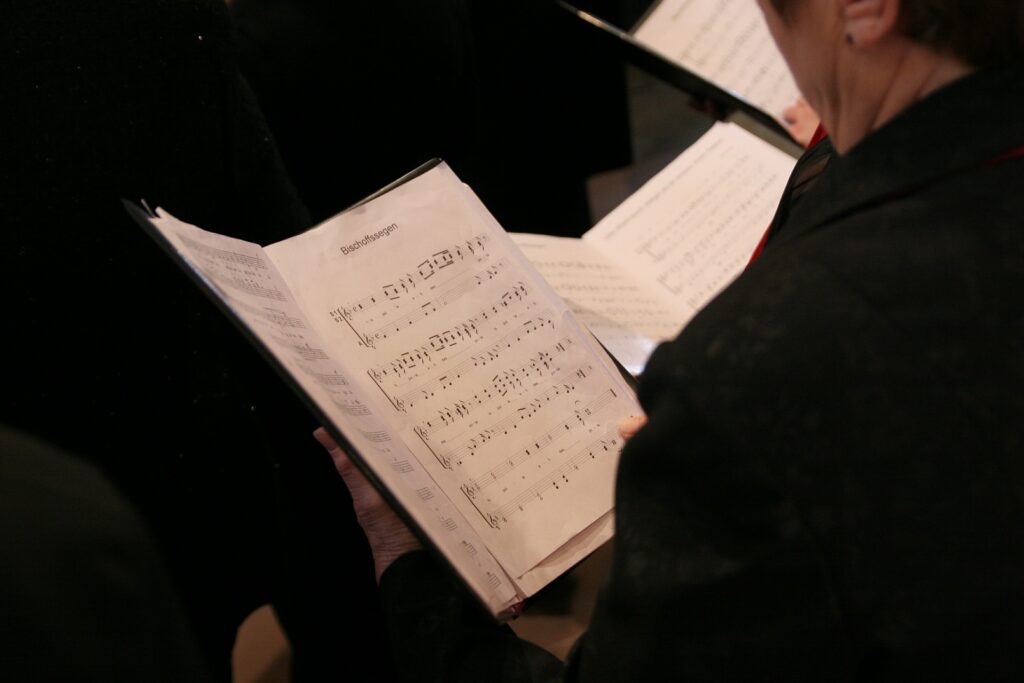

But the bit that really got me, I must confess, was the BBC Singers. There they stood, spread across the vast distances of the stalls, with not a page of music in sight, whilst Nicholas Chalmers led them through a performance of Eric Whitacre’s best-known choral piece. The sound ringing through the space was utterly radiant, the performance immaculate… and when the orchestra applauded them at the end, I was completely choked up. Next time there’s a BBC Singers concert I can actually get to, geography and global pandemic allowing, I intend to be there.

As it happens, I’ve spent time over the last few weeks speaking to several other leading choral composers for another project I’m working on (and was also lucky enough to meet Eric Whitacre several years ago), and have been struck all over again by how much the choral world has its head screwed on in a way that quite a lot of the rest of the classical music world could benefit from. So before we get back to the interviews in next week’s blog, here are a few take-homes that might be worth thinking about, that all high-level choral musicians seem have figured out already:

- Just because it’s suitable for amateurs, doesn’t mean it’s Less Good. Most choral singers are amateurs, and good amateur choirs are superb. It’s possible to not get paid for something and still be fantastic at it. (The converse is also true: see, for example, most senior members of UK government.)

- A piece can be written for a very specific occasion and yet still be adapted, with the composer’s happy assistance, to be performed elsewhere. Getting hung up on specifics is not always helpful; finding practical solutions that work is more important. Actually, pretty much all performances work on this basis, but it’s the choral musicians who are actually prepared to acknowledge this publicly.

- Pragmatism also extends to how a piece is written – idiomatically, in terms of textual clarity, breath, balance, and so on. Writing music is a craft as well as an art, and yeah, sometimes that C sharp is in the accompaniment because frankly, where the heck else are the sopranos going to pitch their C sharp from? This is neither a failing of the composer nor the sopranos, it’s an acknowledgement that you’re writing music for humans, and that collaboration and empathy are good.

- Writing music that people want to sing is a happy endeavour. You are not going to please all of the people all of the time, so writing things that you enjoy writing and that others might enjoy singing is a good thing to aim for. Music is thus allowed to be fun, enjoyable, simple, funny, and many other adjectives that we’re rather less good at applying to, say, Beethoven. (If you’re spluttering in outrage right now, think of the last time that you heard Beethoven’s music described as simple or funny without the full descriptor being ‘sublimely simple’ or ‘cosmically funny’. I happen to think he can be both simple and funny, but in the main, we’re just not very good at saying that.)

Last but not least, a word to those who loved Sleep, and a word to those who hated it. You are entitled to either opinion, obviously. But it’s not A Terrible Piece because it’s not written in high modernism and a lot of people happen to like it. Nor is it automatically A Great Piece because you liked the noise it made more than you did the Copland, Kendall or Beethoven. We make value judgements in music all the time, and what’s crucial is that we’re aware we’re doing it. Love it or hate it, but acknowledge that that’s about you as much as it is about the piece. Sung beautifully by a professional choir, in the circumstances of last Friday, I found it intensely moving. And above all, I just hope it’s the harbinger of more excellent things to come, including (whisper it…) going to a concert soon where I can applaud the composer, conductor, and performers in person.

Katy – I am so impressed by what you have written here, even though it’s taken me a while to come across it! It is so refreshing to hear such a knowledgeable and gifted music writer as yourself expounding the value of choral music written for amateurs. To hear somebody speaking so frankly about the value of music being ‘allowed to be fun, enjoyable, simple, funny’ is music to my ears! Away with musical snobbery!

Thank you.

Away indeed! How very kind – thank you Gill!