Let’s Play 7: Wild Plum Arts

So, enough of my solo soapboxing – on with the interviews. I had the huge pleasure of speaking to Lucy Schaufer and Christopher Gillett, both highly regarded performers in their own right (amongst many other skills, as they will reveal imminently). They are also the creators of the production company Wild Plum Arts, which recently hosted its second ever residency at the Red House in Aldeburgh, providing composers with a chance to spend a week working, thinking, talking… and eating the fantastic food that Lucy and Chris provide for them. There is no ‘goal project’ for composers: no performance at the end, and no work to hand in or make available to the Wild Plum team once they’re done. It’s a chance to be creative in whatever way they see fit – a vital opportunity in an environment so driven by commission and prize pots to keep writers writing.

But we’ll get to all of that in due course. First of all, I asked Lucy and Chris to describe themselves – what they are and what they do. Lucy, as a lover of alliteration as well as a multi-talented soul, went for ‘producer, performer and purveyor of fine jam’. Crucially, she is not interested in being regarded only as an opera singer, because she’s doing so much more than that. Plus, as she points out, in this moment when so much is in flux, ‘it gives me freedom to change – and freedom to grow… we have to stop putting people in boxes just so that we can market them.’

Chris acknowledged straight away that mostly he’s earned his living as a singer; but more recently, he’s also done a great deal of writing, as well as directing. He eventually settled on ‘arts handyman’ as his current descriptor, having begun his career with a total focus on singing and gradually diversifying. Lucy, by contrast, was juggling from the start of her university career (operatic work, music theatre, working on Wall Street, teaching – the list goes on). Yet they both agree that they could never have predicted the range of activities that they work on today. Around three years ago, Lucy and Chris started Wild Plum Arts. Lucy had previously run a production company on her own, but this was to be a joint effort with a big idea at its centre.

(N.B. In everything that follows, Lucy and Chris are quoted in combination – they are uncannily good at finishing each other’s thoughts and sentences…)

‘I always wanted to run what used to be called an “artist colony”. That whole late nineteenth-century ethos that started in the States gave us MacDowell and Yaddo (both creative retreats which are still in operation). There have been some stabs at it here, but nothing that has become a long-running “think space” for composers and creatives.’

So with Chris to encourage Lucy to go for it, they started Wild Plum back in 2018. The name is a reference to the wild plum hedge from which they forage every year. As Lucy says, ‘This hedgerow gives to us unconditionally for us to create whatever we want. And the symbolism in that was far too great to pass up.’ That they ended up with an organisation called WPA – like Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration, which supported Arthur Miller, Orson Welles, and many other creatives – was an additionally pleasing coincidence. (And you’ll note they wanted ‘arts’ not ‘music’ as their descriptor, to be as inclusive as possible). Past projects have included ‘The Class of 1938’, celebrating the 80th birthdays of notable American composers, and ‘All About The Women’ in collaboration with PRS for Music and Cheltenham Music Festival. As Lucy says, ‘it’s about building a platform for composers and trying to make sure they get heard, trying to help them with income streams… and talking to the audience.’

This summer also marks the second of Wild Plum’s ‘Made at the Red House’ residencies for composers. So what’s it been like for them? Have people behaved differently this year?

‘The first night fizz when we all say hello usually is about a half an hour of dog’s butt-sniffing, and sort of seeing who’s who, and what kind of games are we going to play… And I found this year that everyone is so hungry for community and chat and connection that they go, ‘what are you doing? Can you tell me about yourself?’ They’re constantly helping and sharing information. And there’s such empathy going on, which I find really great. Because not only are they being human beings with each other, they’re being absolutely supportive colleagues. They talked concerns, but COVID wasn’t the main thing because we’ve worked really hard to eradicate that from their consciousness.’

The set-up for social distancing and care with food, outdoor spaces, and every other aspect of the experience, was immaculate throughout the residencies – and the opportunities that Made at the Red House provided were clearly of tremendous value to its participants.

‘It might seem rather counter-intuitive to be seeking solitude at a time when everybody’s stuck on their own. But it was very moving when we had people coming here who, for instance, had been home-schooling for months, and just needed some space alone to go back into composing. And [this particular composer] said they burst into tears when she pulled up into the drive because they’d made it, they were convinced something was going to stop them getting here. In the evenings, the buzz was extraordinary. So it was a real release I think.’

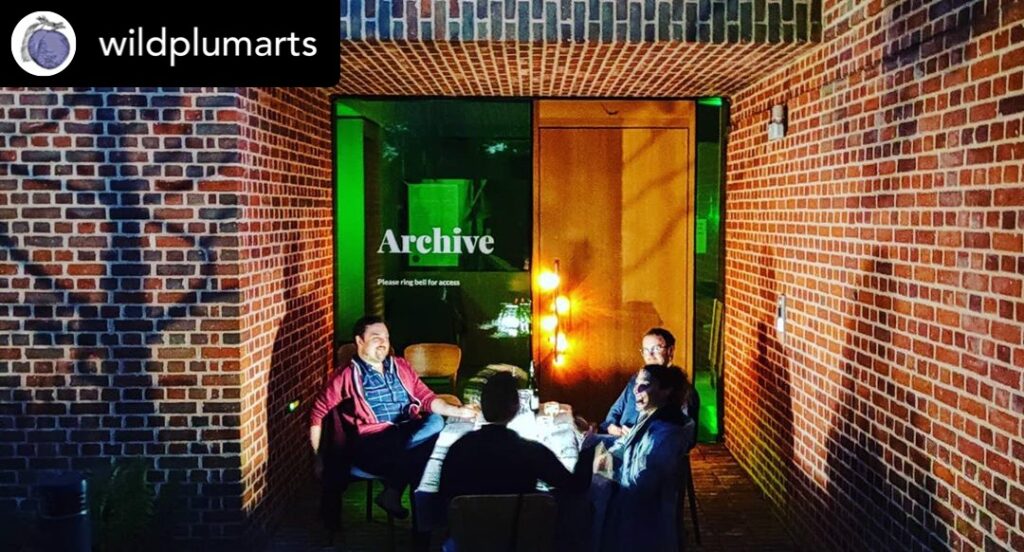

As with Christopher Glynn and the Ryedale Festival, Lucy and Chris mention the flexibility with which smaller organisations can work, and how nimbly they were able to respond to reformulating the set-up to be safe… but also to unforeseen hiccups during their stay. All group meals were eaten outside in the specially christened Benjamin BritTENT – but on the first evening of the third week, it got so windy that the tent had to come down. Chris noticed that the porch of the Britten Archive was nice and sheltered and got permission from the Red House team to relocate their meal there. And voila – it worked:

Flexibility of mind, or ‘make-do and mend’, depending on what you want to call it, is crucial, both insist – as is trying out new ideas and working collaboratively to create despite the current situation. Could the new shorter format concerts being trialled by various venues – Snape Maltings and Wigmore Hall among them – become a way of breaking the old pattern? Chris hopes they will – ‘hearing just two pieces is fantastic, wonderful, you can really concentrate on those two pieces and not feel like you’ve “eaten” too much.’ There’s a strong sense, too, that venues should be taking a chance on younger artists and unusual repertoire, rather than playing it safe for fear of not selling tickets. ‘People are hungry for music.’

So far, Wild Plum have hosted 33 composers (aPlumni, as they should properly be called), and commissioned 13 songs to date – including a new piece to be performed later this month at the launch of Oliver Soden’s book Jeoffry, a fictionalised biography of the life of Christopher Smart’s famous cat. The success of the scheme is partly to do with its compact, ‘boutique’ nature, which means that they can support composers and collaborators individually. ‘One of the composers said the other day, “When you take such good care of us, we feel this sense of gratitude that we must work in order to not waste what you are giving us.”’

So – how do we help?

Money, of course, is always welcome, though Lucy sounds a note of caution about the ‘formalised application language’ of funding bodies like Arts Council England, which are hugely time-consuming and often extremely difficult to complete straightforwardly. Also, as Chris says, ‘Why not let composers be useful? Instead of thinking “I shall buy my husband a new set of golf clubs for his birthday”, why not get somebody to write them a song?’

And then there’s the question of music-making itself. ‘If you have a big space, why not run concerts and find local musicians? Local is important. Local has never been more important. Find people in your area to make music with them. We’re in a renewal phase for grass roots.’

Last but not least, there’s the question of the resilience of the arts. Here, Lucy references a recent article in the New York Times. ‘It says, “being resilient sometimes lets other people off the hook”. Because I can be resilient, I’m letting a person in power off the hook and they’re not taking responsibility for their job. Our industry has been resilient for centuries. So those who are supposedly in power: pull up your socks. Because it’s time for you to actually give more, not less. Everyone needs to be resilient together – and also innovative. And if some things have to go by the wayside for a while, I’d hate to see any orchestras or organisations go, but that may be just part of clearing the forest. Sometimes things die in a fire. And then they regrow in different ways. And that’s ok. It hurts at the time, and it hurts greatly, but other things can grow up again. Maybe this is a new phase.’