In print… and how we got there

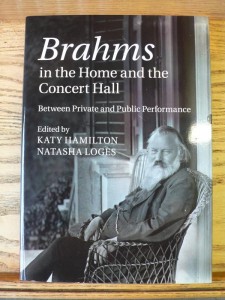

This week, something VERY exciting has happened. Ladies and gentlemen, I present the first book in the world which has my name on the cover. Hurrah!

Brahms in the Home and the Concert Hall is a project some four years in the making, from the conference in 2011 that prompted us to consider a publication, until just two days ago when it appeared in print. It involved a tremendous amount of work from a truly wonderful, passionate, careful, dedicated group of researchers and writers, who were almost invariably charming and accommodating in dealing with editorial requests. We had the input of professional music setters, the co-operation of the Johannes Brahms Gesamtausgabe (Collected Edition, published by Henle), and permission to include images from world-renowned collections. As a co-editor, I couldn’t have wished for a more supportive, hard-working and creative person than Natasha Loges. The end result is a real work of art – musical, literary, scholarly and visual – and I’m immensely proud to have been a part of it.

The process of making a book in this way, with 14 contributors and 2 editors, is an education in many directions at once. There is the basic question of how one puts together a book proposal, and how much content needs to be in place before a publishing house will accept it. Once the project has been accepted, you then have to set realistic deadlines (and the writers’ idea of realism might vary from the publishers’, although we were very fortunate in this regard). There will inevitably be queries from authors. How many pictures are they allowed? Music examples? Is the word limit they have been given really set in stone? Can they include original language quotations in footnotes if they have provided an English translation in the text? And actually, will they be footnotes or endnotes, and how will that affect what they include in them?

At the heart of all of these issues lies the most important, I think, for multi-authored works. Communication. If everyone feels that they are fully involved, and that their queries and concerns are being listened to, inevitably the working environment will be easier. This was of particular importance for us co-editors, since Natasha was out of the country for a year and this necessitated frequent emailing, Skype chats, and visits to Berlin (a great hardship, obviously, particularly given the proximity of her flat to an extremely good chocolate café). And not only were we editing the book together; we were also writing a chapter together. That is a very particular kind of discipline, and finding someone with whom a workload can easily be shared, and creative ideas can freely be incorporated, is a rare and exciting thing.

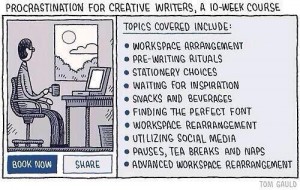

So aside from all the administrative jobs, from library permissions to fact-checking; and the proofing tasks, like making sure everyone had used the right kind of dash; and the task of trimming and adjusting paragraphs where appropriate, and ensuring that authors were happy with this, there was also the business of writing. Anyone who has ever tried to write anything, from fan fiction to biology textbooks, can probably relate to this:

And here was the unexpected corollary of being so involved in the… mechanics, for want of a better word, of producing a book. The nuts and bolts, the careful checking for typos and index terms, the communication with authors, music example layouts, and so on – these things are all vital, but they are also peripheral to why you are writing the book. And they are also relatively low on intellectual input, and satisfying to do. You feel as if you have achieved something when you’ve checked through all those illustration labels, and for relatively little effort. But writing? Writing is slower. It takes a great investment of time, not only in the research and planning, but in ensuring that the shape is right, that readers are led easily and elegantly through your argument. It is fascinating, and frustrating, and time-consuming. It takes practice. It needs space, too – the opportunity to write, go away, come back in a few days and decide if you’re happy with that earlier effort. And that is why we can be prone to procrastination, because writing involves such a deep engagement with material (which is tiring), can take days or weeks – or even months – to finalise (which can seem like too much time for too little reward), and because at root, it’s a little bit scary. It needs to be right, both in terms of its factual content, and in its representations of our thoughts and arguments. You need to be brave to write things.

So as Natasha and I raise a glass to Brahms tomorrow evening, and celebrate the appearance of Brahms in the Home and the Concert Hall in print, I will consider myself extremely fortunate to have been a part of the project, and proud of the outcome. It’s been a real journey, and one I hope to make again some time very soon. But when the book finally lands on my doormat in a few days’ time, don’t ask me to read my chapter. Anyone else’s for sure, but not mine. Not just yet. Reading what you’ve written, once it’s in print? That’s a whole extra level of bravery.

***

Brahms in the Home and the Concert Hall is available to buy via the Cambridge University Press website, and extracts are also available to view via Google books. An e-book version is also available via both sites.